At 6:00 a.m., the alarm goes off in the yurt.

It’s time to utilize the cool morning air in an effort to cross off a never-ending to-do list. “I get up early because the yurt has no air-conditioning,” says Samantha, East Austin yurt dweller, who crafted her home with the help of her friends and community.

Traditionally used by nomads living on the Mongolian steppe, a yurt is a modest-size mobile shelter that is traditionally made of a circular wooden frame wrapped with fabric, felt, or wool for insulation. For Samantha, the yurt, with its many “bumps and lumps,” is home.

Story and Photos by Kali Miller

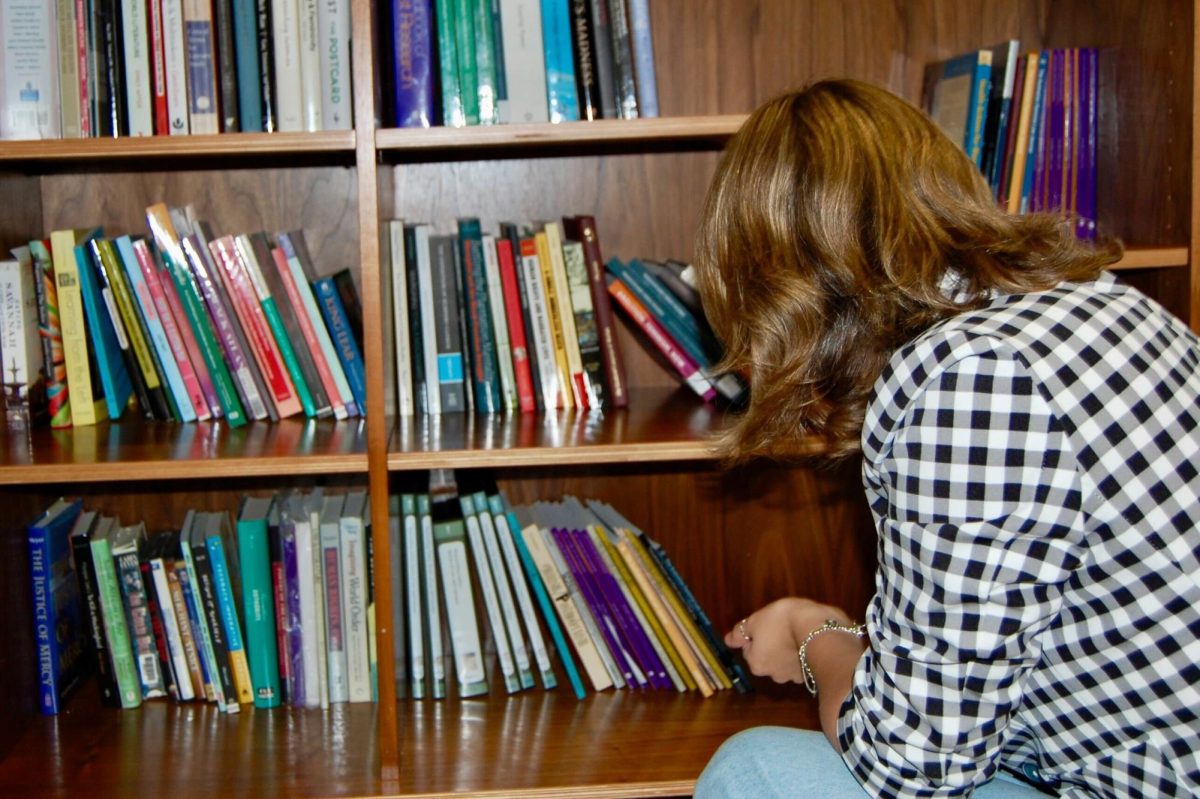

After a cup of coffee and morning meditation, Samantha gets to work gardening, bee-keeping and mapping designs in her notebook. Albeit city regulations, Samantha set up in the yurt in a woman’s backyard. Her landlord charges low rent in exchange for Samantha’s help and innovation in the garden. The low-cost lifestyle of yurt living allows Samantha time to pursue projects of interest. In fact, she describes her living situation as something of an “experimental” project.

Inspiration to experiment with her lifestyle stemmed from multiple facets in Samantha’s life. “I got out of a bad relationship and needed a place to live. Apartment living was too expensive, [and] between rent and food there was no money left to experiment with,” she says.

But the motivation for such a dramatic lifestyle change was rooted in something deeper. While studying environmental justice at Hampshire College, Samantha felt a yearning for social change. “After studying development and history, neocolonialism, economics and social movements, I realized it’s all about how we feed ourselves, and how we live in balance with ecology and each other,” she explains. This realization sparked Samantha’s interest in sustainability of the earth’s resources — land, food and water — and prompted her to study permaculture, which she describes as “a different way of living, relating to the world and to each other [by] integrating functions and biological processes using smart design, without the back-breaking labor that farmers experienced in the past.” She adds that permaculture is a large contributor to the sustainability of the yurt.

Propelled by necessity, many of Samantha’s “permaculture” projects face the challenges that living in a yurt presents. During the summer, Samantha built a pond in the backyard to find relief from the heat. She designed the swimming hole to double as a veggie-growing hydroponic system that sits on top of the swimming area and allows water to trickle down in a calm stream. The water then circulates back to create a continuous movement that aerates the water and nurtures plant growth. “On a hot day, it was perfect to hop in the pond with a couple of friends and a beer,” she says.

Now as the weather cools, Samantha focuses on developing heating strategies that will keep her “off the grid.” In other words, she does not want to hook up a generator for energy and warmth. She is currently investigating radiant heat tubing. This heating method uses a solar panel oven that captures heat from the Sun, which is then distributed to water that flows through plumbing tubes. Samantha plans to set up these tubes in a coil formation underneath the yurt. “The yurt is not super insulated, but because it has a small surface it will trap heat. I’m not a plumber, but I’m figuring it out. I ask questions. I YouTube,” she says.

For now, the yurt is hooked up to a water storage tank outside that allows for cooking and sink use. Samantha uses around five to ten gallons of water a day, compared to the average American’s 150-gallon daily use, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. To further increase her water sustainability, Samantha is researching rainwater harvesting, a process involving catching the rainwater that flows off the roof.

Although Samantha says her lifestyle is incredibly sustainable, it is not yet capable of singularly providing for all of her needs. The garden produces a substantial amount of food, but “there’s still a lot of tacos involved,” she says. To provide for rent and other needs, Samantha relies mainly on her main source of income — an agricultural landscaping business.

Because of her low-cost lifestyle, Samantha focuses on what intrigues her. Currently, she is helping a friend retrofit a garden in return for duck eggs. This type of bartering, she believes, propagates good quality service on both sides of the spectrum and develops a level of trust between people in the community.

After living in the yurt for nearly 5 months, Samantha has realized that there’s not a guidebook for how to live a simple life and reclaim what you truly value. But, she explains, “it is possible to live simply and give back what you take.” Samantha suggests that the best way to do this is to “examine your priorities, see if your lifestyle aligns with those priorities, and, if not, find the best way to make a sufficient change that is emotionally, physically, and financially possible for you.”

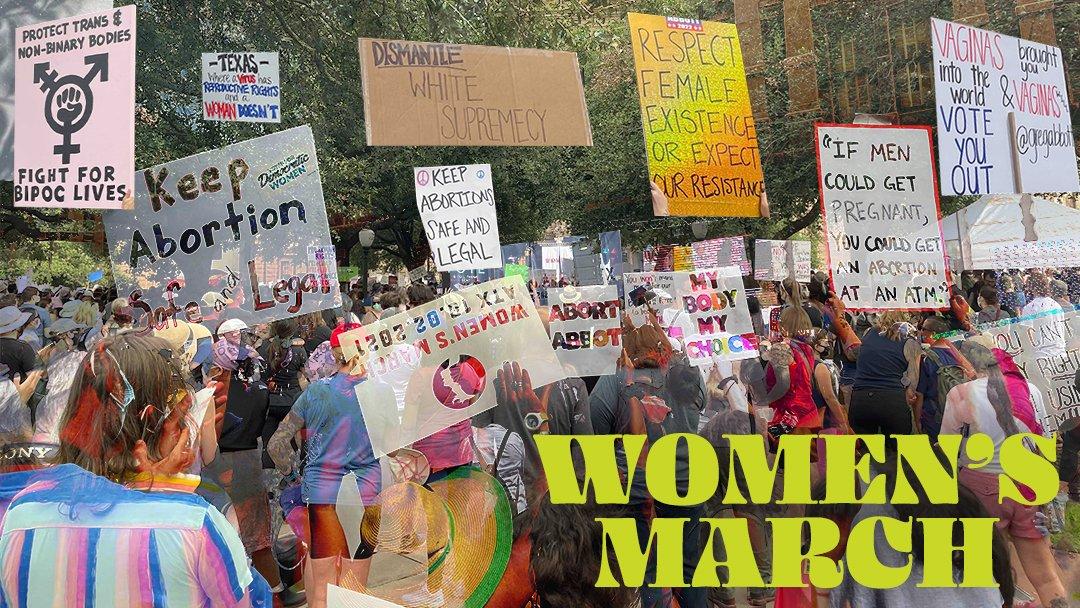

Although life in the yurt may seem hunky-dory, the current development and gentrification (i.e. the transformation of a community that pushes out old residents and benefits new residents) in East Austin may threaten her way of life. In the future, Samantha pictures herself moving out of Austin and potentially packing up the yurt, much like a nomad.

“I like to look at life in two year increments. Anything beyond that freaks me out,” she says. Until any definite plans form, Samantha focuses on her daily life, living in a manner that doesn’t only “talk the talk,” but “walks the walk.