We’re just girls, of course we have obsessions.

Some obsessions may include sports, reading YA fantasy romance novels, or owning a stan account dedicated to posting photos of Harry Styles.

The term “stan” originated as a negative combination of the words “stalker” and “fan,” aimed toward obsessed fans. Now, the word has taken a positive form, as a label for someone who shows a lot of enthusiasm and dedication to something. At the end of the day, as long as you’re happy, who are we to judge?

Well apparently, many people judge. Among the many negative impacts of patriarchy and misogyny, degrading women for having interests is one of the most disappointing. Men hating on the Barbie movie for being “anti-man” and reversing societal gender roles, or male talk show hosts stereotyping young women for going crazy over an idol are all examples of this trend.

The anti-fangirl agenda has occurred in different surges. There was the Justin Bieber era, where people called the fandom delusional and accused them of having the hysterical “Bieber fever.” Then came the One Direction wave, where Directioners were seen as obsessive and dangerous.

Most recently, BTS fans have been getting the same treatment. Talk show host James Corden joked on “The Late Late Show” that, since BTS had planned to speak at the UN, “15-year-old girls everywhere” were going to dress up as security officers just to see them. BTS ARMY fans were upset and felt like Corden was portraying them as obsessive little girls rather than supportive fans.

The hate isn’t just toward fans of male artists. For her entire career, Taylor Swift and her fans have been criticized for getting overly emotional. Now that she’s dating football star Travis Kelce, it has gotten worse as football fans have started to criticize Swift and her fans for degrading the sport

“You’re ruining football,” a Ravens’ football fan said to Swift at a game as she walked through the stadium hallway.

This is far from the hate fangirls get online.

Someone on Quora posted, “When I say ‘I hate fangirls because they drool over celebrities and gush over fictional character relationships,’ does that make me sexist?”

Just asking that question sums up the issue. Saying that fangirls “drool” and “gush” are already stereotypes towards women that men don’t have to face. Men have fan cultures too, where they scream, cheer and cry for joy, just like fangirls.

“Why do straight men always demean fangirls and pop culture when they act like this at soccer games,” a Reddit user queried on the board r/popculturechat.

They shared a video alongside their post of a soccer player turning to wave at a mostly male audience, who passionately cheered and waved back, enthusiastically embracing the athlete’s attention. This behavior is similar to fangirls crying over their favorite pop-star, yet these men face little to no backlash for reacting this way.

No community gets more heat for being “obsessive,” or “controlling” than K-pop fans.

The K-pop fan community began small, even as the genre became widespread due to the popular hit “Gangnam Style” by Psy in 2012. After BTS attended the Billboard Music Awards in 2017, they became heartthrobs for many.

The K-pop community on X, formerly Twitter, started to thrive as random people saw BTS’ red-carpet pictures and began asking who the young band members were. Some felt the need to gatekeep the band, but many in the BTS ARMY community responded with the member’s name, eager to grow the fandom.

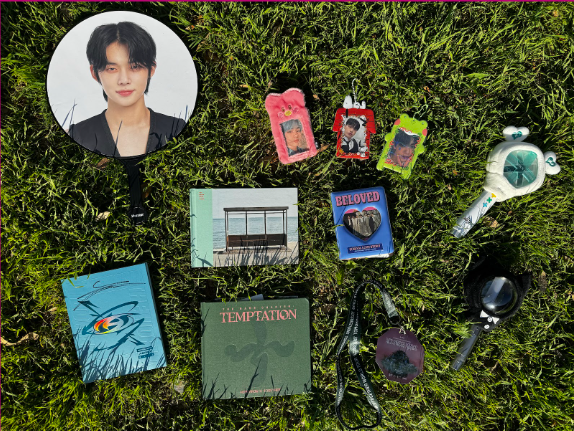

Since then, the K-pop community has expanded as fans grow to like other K-pop groups besides BTS, leading many K-pop fans to embrace their inner fangirl. Many fans have taken to X to tweet pictures of their favorite member’s merchandise alongside other items they carry in their bags, declaring themselves proud fangirls.

My fangirl journey has been a long, never-ending rollercoaster filled with highs and lows. There were the early days as a Directioner in middle school, but tragedy struck when the group disbanded a year after Zayn left in March 2015. I suddenly had no one to stan. About two years later, fangirling came back to me after discovering BTS and the world of K-pop. It was as if being a fangirl was always deep in my core.

BTS and K-pop saved me during tough times as I transitioned into high school by creating a separate community to go to online when I felt alone. I fell away from K-pop in my junior year but fell back into it during COVID as if I never left. It comforted me in times of uncertainty and kept me going every day in quarantine. Even to this day, having a community online and being able to check updates on X is genuinely what helps me wake up in the morning.

I still remember how emotional I was after seeing one of my favorite K-pop artists post-quarantine. Singing along to the songs that comforted me during hard moments felt surreal. Being united with so many other fans who felt the same was incredible. Now, when I’m inside a K-pop venue alongside other K-pop stans, it feels like home.

“I like the sense of community I feel whenever I go to events like concerts. (There’s) something about knowing that we’re all here for the same reasons,” said third-year biology major Melissa Trang. “I don’t know how to describe it, but that sense of belonging is fulfilling.”

There’s also happiness found in standing in line hours before a concert, watching K-pop dance covers, or receiving handmade freebies, similar to the way Swifties exchange handmade bracelets. There’s joy in opening albums and collecting surprise member photo cards, just like one may find excitement in collecting baseball or Pokemon cards.

Making deep connections with artists may make fangirls seem overly emotional, but we learn to embrace it. On X, a video surfaced of a Swiftie crying into her friend’s arms as she listened to Swift’s song “Exile” outside a concert stadium. The fan said the song saved her life.

Some on social media saw it as overdramatic, but many different fangirl communities came together and reposted songs they’d reacted to in similar ways. K-pop fangirls were quick to jump on the trend and reposted ways they could relate.

“Fangirls” and “obsession” are both words that go hand in hand, either stereotyped by men or rejected by women. However, I’ve come to embrace them. I’ve learned that healthy obsessions that don’t include being a “crazy stalker” exist, and that they can be a stress-relieving, happy outlet. Being a K-pop fangirl is my healthy obsession, and at the end of the day, I’m proud that I’m a Yeonjun girl.