Students and faculty who attended “Nasty Talk.”

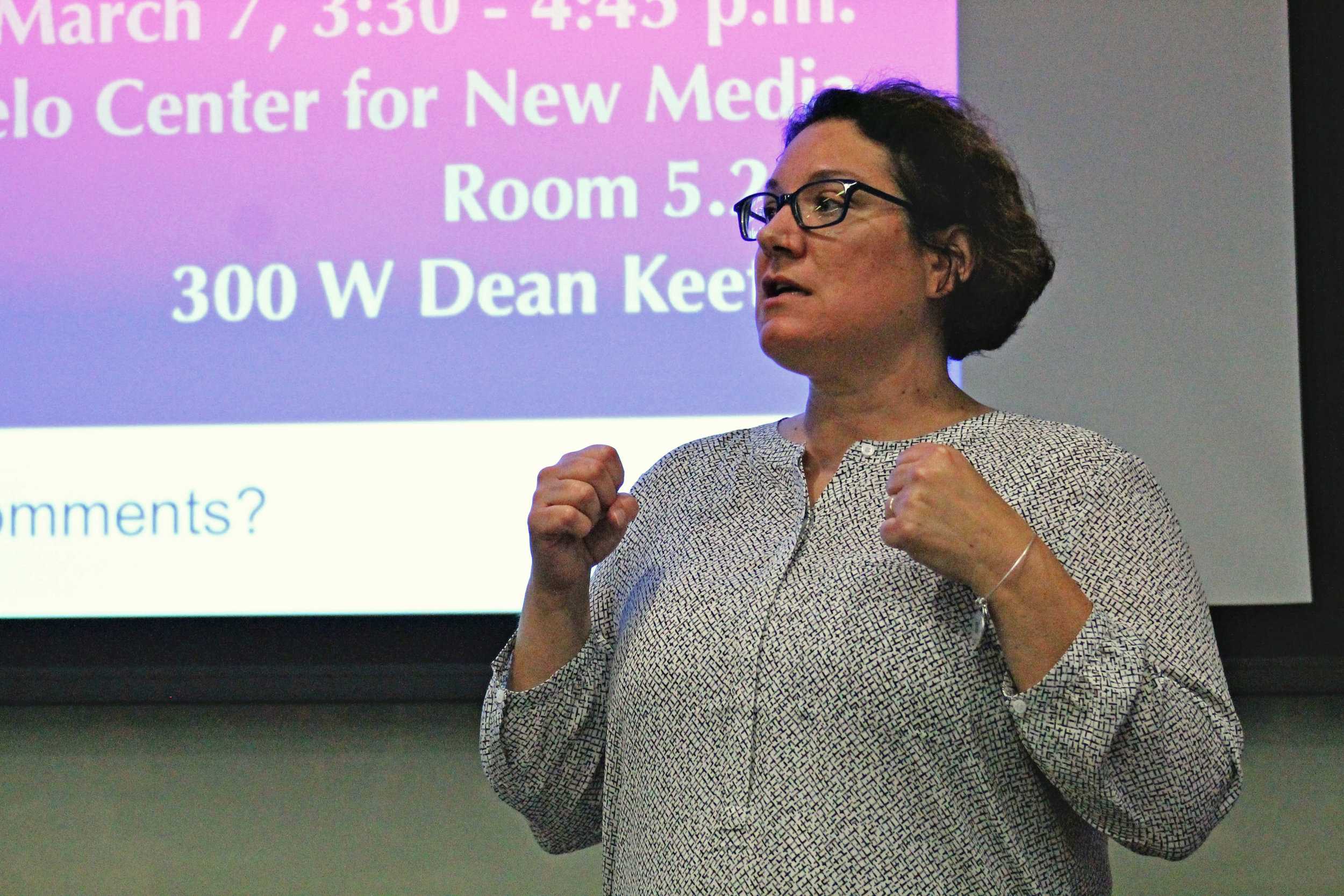

On Tuesday Mar. 7, Gina Chen, assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin and former journalist, led the “Nasty Talk” forum over online political incivility.

Story by Urub Khawaja

Photos by Laura Godinez

Online political incivility has been a common occurrence, especially as a result of the of the recent outcome of the U.S. presidential election. There are three main types of incivility online: profanity, insults and name-calling, and potential for racist, sexist, homophobic and xenophobic speech.

Though political conversation can be unpleasant, there are some benefits of engaging in it. These online discussions can be valuable to people who are undecided on their stance. “There is a swath of people who can be persuaded or, at least, informed,” Chen says. “Most people who have really really strong opinions about something—you’re not going to shift them with a tweet. You’re never going to shift them with a tweet. But, there are some people who do not have strong opinions about things.” According to Chen, communicating viewpoints to those who are less informed can help them sharpen their thinking and gain a better understanding of other perspectives.

Political debate can result in people congregating and taking on certain opinions without knowing exactly why they have chosen to side with a certain political party. “They jump on the bandwagon, but don’t really know why,” Chen says. “That’s one of the problems when people start calling their elected officials, and they don’t really know what to say, because they’re like ‘I know I’m for this’ or ‘I know against this, but I don’t know why.’”

Journalism professor Gina Chen at her “Nasty Talk.”

According to Chen’s research, when a person is exposed to disagreement, it helps that person determine how he or she thinks. “There’s lots of research that shows that when you’re exposed to what you don’t agree with, it makes you say ‘Hmm. Why do I not feel that way?’” Chen says. “And then it sort of makes you think about your own beliefs.”

In order to better educate people, these online political conversations are necessary to help people form their opinions with adequate reasoning. However, Chen also says that the Internet can be an “inhospitable place.”

She gives the example of actress Leslie Jones, who was hacked on Twitter and received hateful comments about herself and her recent movie “Ghostbusters.” “She ended up having to quit Twitter because she got so much hate, and one of the people that was leading [the attack against Jones] actually got banned from Twitter for life for instigating this,” Chen says. “I don’t want to create this Pollyanna view—there’s real trouble with the Internet. I’m not talking about the value of bullying people online, or trolling people, or using hate speech—I don’t think there is value in that.”

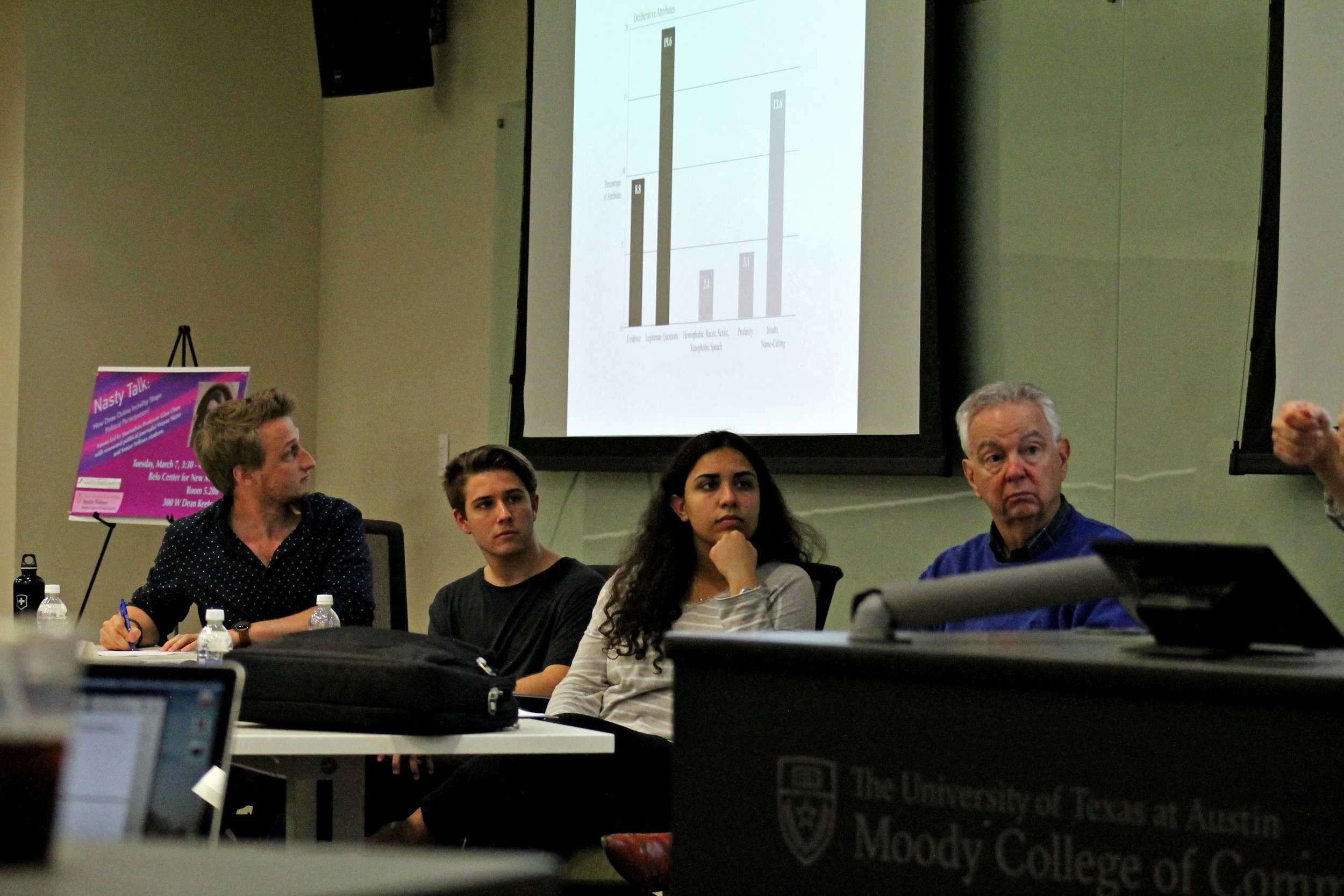

Panelists ready to ask Professor Chen questions.

Chen found that according to Kelly Stratton’s research on journalists interacting with reader comments that it works well when journalists use humor and humanize themselves. “I think when a journalist is on the site and commenting on the story, even just answering questions, people are less likely to force off another opinion,” Chen says.

After Chen’s talk, Wayne Slater, former political reporter for the Dallas Morning News hosted a panel discussion along with students of the Senior Fellows Honors Program. As a reporter, he also received impolite comments on his articles. “I’ve gotten my share of comments that say ‘you’re an idiot,’ or ‘you’re just totally wrong,’” Slater says.

Last year, NPR turned off commenting for its readers because less than 1% of its audience was commenting on its posts. Angela Fayad, third year advertising student, believes that news organizations will tend toward comment censorship in the future. “I think other news organizations will find creative ways to close off opportunity for conversation in pursuit of cleaner dialogue,” Fayad says. “I think the inclusion they seek can only happen if people are allowed to debate online and see how others think. Otherwise we are left to mull over articles ourselves and have the potential of becoming a one-person echo chamber.”

Though online political incivility can cause much instability, Chen says that she would much rather have that if it is the only way to get people to be politically active. “We, as a country, are not politically engaged enough at all, despite the fact that recently people have been,” Chen says. “If people have to be nasty to get revved up to vote, I’d rather them get nasty—not everyone would say that, but I’m also somebody who’s more comfortable with that—because ultimately I think for our democracy, people need to be engaged in the political process.”