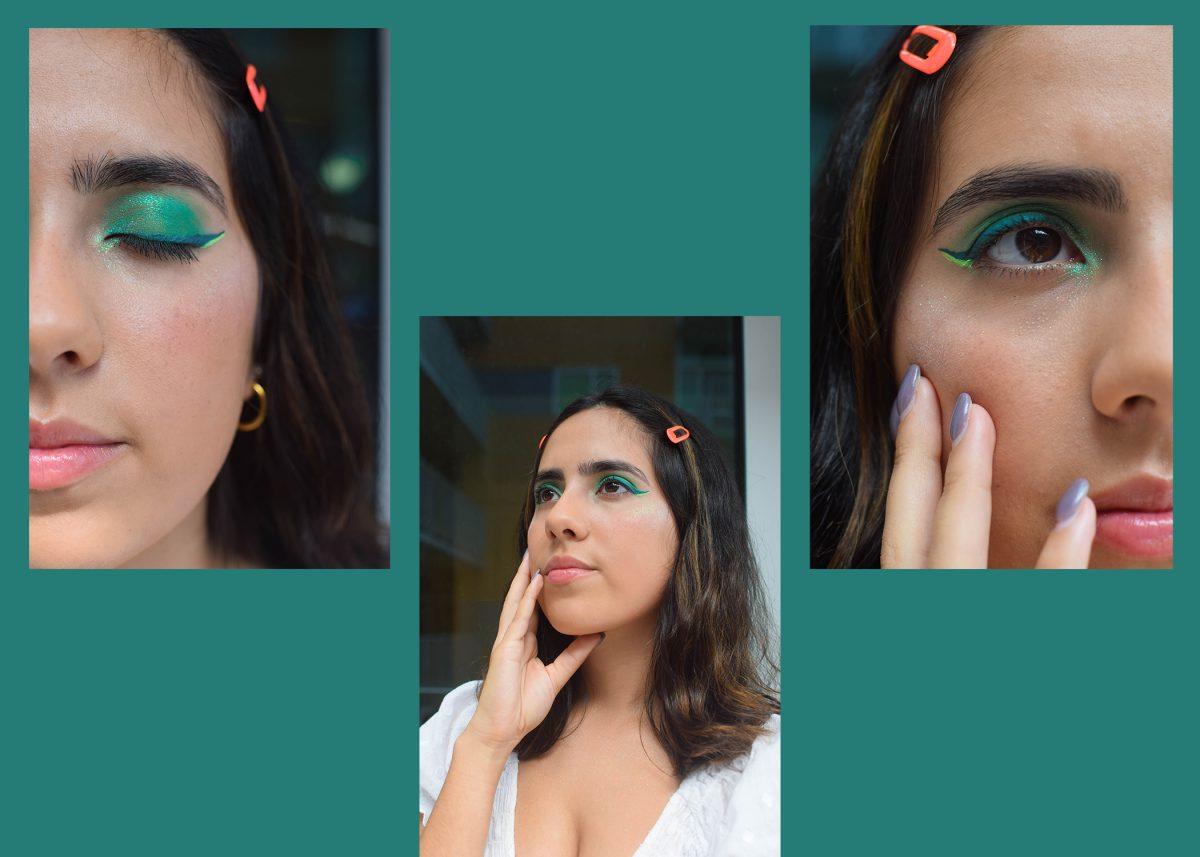

Thursday afternoon, a smiling girl with long brown hair leads her 3D film class in a workshop. With an intense look of concentration and an unbreakable train of thought, it’s utterly fascinating to watch her work with the camera. Like an artist creating a masterpiece, Hannah Whisenant’s concentration cannot be broken, except, of course, when she laughs at something particularly amusing.

By Alexa Harrington

Early Saturday evening, a typical student film crew shoots a class project in a hot, cramped West Campus apartment. The atypical female leader of the crew lugs around a cumbersome 35mm camera, which is completely disproportionate to the size of the apartment and to the size of the woman carrying it. As she gives orders to the male technicians, the tall and slender Nikki Dengel maintains her grace and femininity while asserting her dominance.

It wasn’t until she watched the University of Texas at Austin School of Communication graduation ceremony that Dengel realized the Radio-Television-Film (RTF) major is a fairly balanced major between men and women.

“I’ve never had better than a 5:1 ratio [of men to women] in class, so I always kind of assumed that there are more men in RTF,” Dengel says.

Referring to classes like advanced narrative, directing workshops, and cinematography, both Dengel and Whisenant say there tends to be a lack of women. Gravitating toward producing, sound, editing and effects, women typically tend to take these classes, they agree.

In 2013, women accounted for only 16 percent of all directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers and editors, according to The Celluloid Ceiling, a study of women’s behind-the-scenes employment in film, conducted by The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University.

If the number of men and women in RTF is about even, then where are all of the women in film going after they graduate from college?

“I think that sometimes girls are intimidated by the guys being more technical, so they feel less comfortable in [technical] classes, and then they don’t end up learning those skills, and then they don’t pursue it,” Whisenant says. “Guys typically get into production, camera and gripping and gaffing stuff, and there are a lot of opportunities for that.”

It’s these technical jobs that act as a shoe-in to the industry. If women are not learning these technical skills in school, it is easy to see how making their way into the film industry would be difficult.

However, Dengel says, “There is nothing about UT that ever discourages women. No one has ever said to me ‘You should be doing producing rather than directing, or this rather than that,’ but I think that women are frequently taught to play it safe while men are taught to take risks and follow their dreams. It’s kind of cheesy — ‘follow their dreams’ —but it’s true.”

“I have a guest female teacher for my 3D film class right now. I really like having her and I like that she does stereography, which is a very technical job,” Whisenant says with excitement. “We really connected. I didn’t think having a female teacher would affect me until I had one.”

UT employs several female film professors — Kat Candler, Ellen Spiro, Nancy Schiesari, for example — but men mostly teach the production classes, and those few women are the exceptions.

Dengel has noticed that a lot of female students choose to have a female professor when they have the option. For example, Schiesari’s narrative production class has a better ratio of men to women, according to Dengel.

“I don’t know if that’s because she’s a woman or not, but I mean, it’s kind of nice to have a female role model to look up to,” Dengel says.

Dengel’s role models include Farah Khan and Kat Candler.

“My one celebrity, big-name role model is Farah Khan. She works in Bollywood. She started out doing choreography, but she recently started writing and directing and has been a big success. I love her movies more than anything,” Dengel says. “When you listen to interviews with her, she’s very aware of her place in the film world… She’s Muslim whereas most [Bollywood] directors are Hindu, but she’s never antagonistic or bitter about her minority status, and she slowly works with the system to bring out better changes about the portrayal of women in film.”

Candler, besides teaching at UT, is a writer and director. She also founded Women In Cinema, an official UT Student Organization that provides mentoring and workshops in camera, lighting and sound for student filmmakers.

Women in Cinema helps women connect with each other and work in positions they might not have normally been interested in.

Through Women in Cinema, Whisenant was able to work on an all-female set, which was a nice change from the usual male-dominated nature of filmmaking.

“On set, sometimes it’s hard to feel comfortable when you’re one of the only girls,” Whisenant says. “I feel more pressure of not messing up or looking like I don’t know what I’m doing because I’m the odd man out.” (Or rather, the odd woman out.)

On the other hand, Whisenant says finding a woman to fit every role for the all-female set was difficult. As one of the women interested in the more technical positions, Whisenant noticed that some women in RTF end up being competitive with the other women on set instead of working together to fill a wider variety of positions.

“I think we feel like we have to prove something because we’re girls, and it keeps us from lifting each other up,” Whisenant says. “But I’m happy to see more girls in RTF, and I think we should really band together.”

Dengel agrees that women in RTF and film in general should support each other.

“I think that if you can’t trust your teammates, you’ve got no one,” Dengel says. “We’re all a team and we are all in this together.”