Amado Peña, Mexican and Native American artist, shares his journey to find his home over a cup of coffee.

Story and Photos by Alejandra Martinez

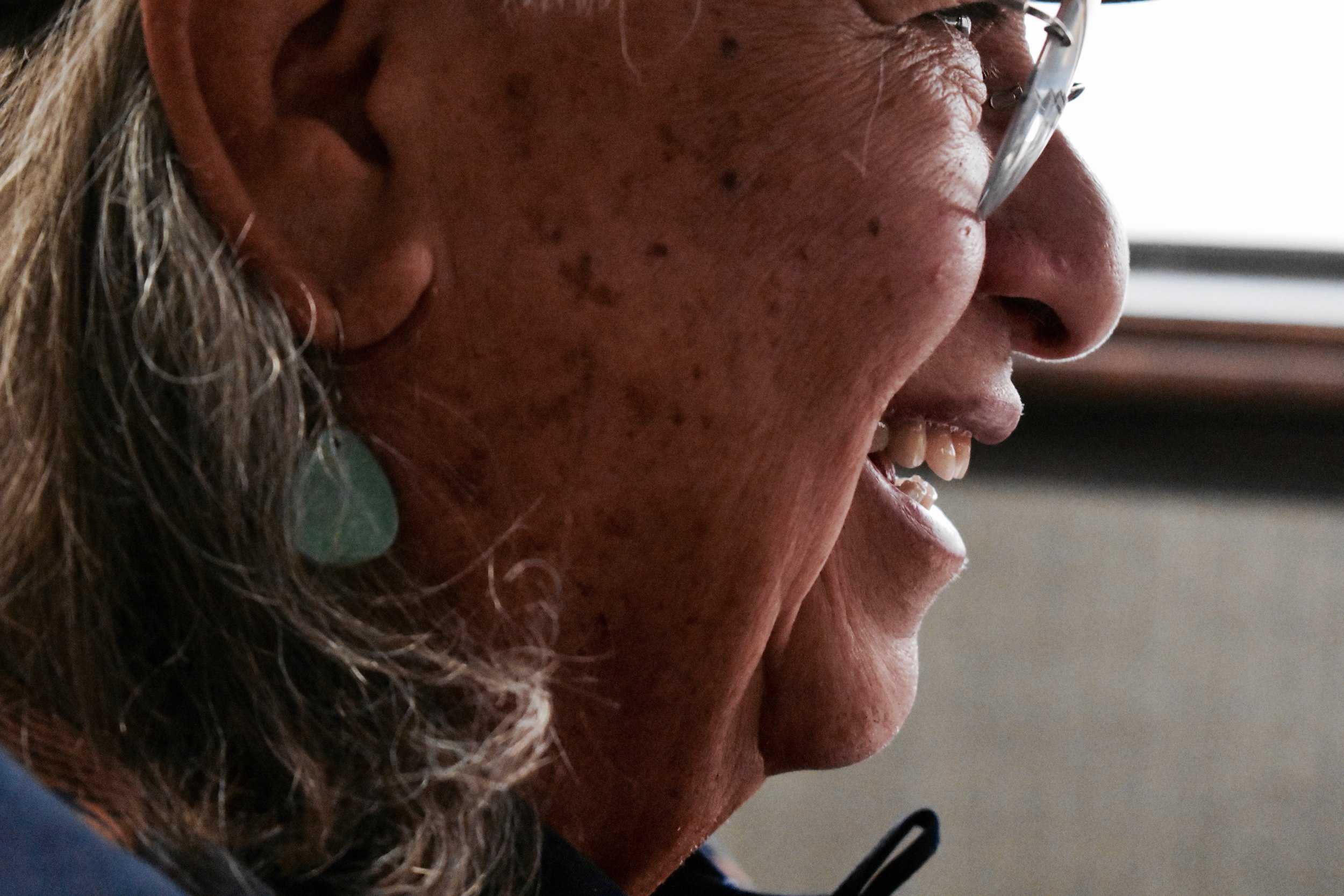

In a navy blue shirt, western boots, dangly Native American turquoise earrings and a hat with his studio logo of an indigenous native, the six-foot, grey-haired, 74-year-old’s history can be seen all over his body. His name is Amado Peña and he is an artist with over 50 years of experience.

There are many aspects to a Hispanic racial identity and for Peña, his attire is just one form of expression. “In our profession, what we do is what we wear,” says the Mexican and Native American artist.

Peña is a cultural icon that has been greatly admired and celebrated all over the world. He describes himself as a people’s artist, joking that he is not sure what his fans mean when they call him “famous.”

Peña earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in studio art and education and opened his own studio inside his apartment in 1965. Since then, he has specialized in painting, drawing and printmaking. His early work included politically-driven pieces inspired by the Chicano movement, which have earned countless awards, including the Hispanic Caucus Outstanding Latino Cultural Award in New Mexico. Most recently, Peña has dedicated his time to create imagery to express his Native American roots.

According to a Pew Research Center report in 2015, 1 in 4 Latino adults say they consider themselves indigenous or Native American. The report also explored the multidimensionality of racial identity among Latinos, the challenges in capturing Hispanic racial identity and explaining it to others.

Peña is one of those individuals who has faced challenges with explaining their identity. He was born and raised in Laredo, Texas, mostly in the Mexican-American cultural traditions of his father. “Everyone assumed that because my first language was Spanish we all came from the same place,” the artist says.

It wasn’t until Peña grew older and started learning about his mother’s Pascua Yaqui identity that he began to self-identify as indigenous. “For many of us [Mexicans] the border crossed us, and for others we crossed the border, so we inhabit a number of identities simultaneously,” says John Moran Gonzales, director of Center for American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

According to Moran, there is a huge problem with America’s categorization of individuals. “The black and white binary makes it hard for many Latinos to explore their full identity. They find themselves not within the system of identification,” Moran says.

For Peña, art became his journey to self-discovery and his system of self-identifying.

Peña’s mother shared stories with him about the constant oppression the Pascua Yaqui tribe faced. According to her, the tribe easily assimilated in Tucson, Arizona because they were a Spanish-speaking population. However, as time passed, the Yaquis grew tired of trying to fit into a culture they did not belong to. “They were completely different than the Mexicano and they wanted to identify themselves as a unique population,” Peña says. From there, they started the difficult task of gaining recognition as an official Native American tribe by the government.

Moran explains how European colonization led to a greater unification of indigenous peoples. There was a bigger sense of pride that was created when Europeans tried to destroy or suppress their identities.

For Peña, gaining that pride and connection to his indigenous ancestries was expressed through his art. He says he began to ask his mother more about his roots, socialize with the indigenous community and read more. “I developed a need to be curious about my Native American identity. That part of who I am needed to be looked at,” Peña says. With his newly gained knowledge, he then attempted to answer what it meant to be Native American within his own unique identity.

Peña described the process he had while creating this recent work. “It’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle; you are answering one question after another and at the end you have this image that you created as of a result of these questions and ideas,” Peña says.

Peña is not the only one who has gone through this process. “My identity has fluctuated over time,” says Angela Lorena Vela Arce, Mexican American studies senior and director of Native American and Indigenous Collective at UT. “Even as a kid for whatever reason something called out to me a lot and I would ask my dad questions about different plants, what prayer meant for our community and how to heal cultural illnesses. I learned about my indigenous roots through oral history.” Arce identifies as indigenous from Northern Mexico and South Texas and says the influences and vicarious experiences she learned from her father and grandma have shaped her identity.

Angela Lorena Vela Arce, director of Native American and Indigenous Collective at UT, was raised Hispanic, but as she grew older she learned about her indigenous roots through oral history.

Arce has recently been awarded the opportunity to feature her research on the U.S.-Mexico borderlands and indigeneity in science fiction at UT’s Graduation Association Competitive Literature conference. She hopes artists, researchers and writers continue to feature indigenous work and express the huge necessity for people to become aware of the indigenous community.

Throughout Pena’s career, the artist has faced some criticism for switching from his most recognized work, politically-driven Chicano art, to a more historical documentation of Native Americans. “Up to a certain point he was an activist in the United States and the change in style for many meant he had given up, given in and sold out to pursue his career money,” Moran says.

However, Peña articulates the importance of his need to step away from that movement. “The imagery and the message was so intense, there was a need for a change. I was drained physically and emotionally,” he said. The artist took this change as an opportunity to learn about himself and take care of his mental health.

Peña’s style then transformed into capturing colorful and soulful images of the Pascua Yaqui of Arizona tribe. He emphasized his new excitement for his work as he explored new parts of himself and his identity. “I really do think those criticisms are shortsighted,” Moran says. “Indigenous people can also be Mexican or Hispanic. He shifted to this other work as a space of self-healing, and it is still engaging work.”

In Peña’s journey, it was difficult to explain his racial identity through art. He was criticized but realized the need to document the history of the Native American communities. His work has become a tribute to his Native American people who have survived and showed strength through harsh realities. “For me, I really feel that I found a place where I am happy with my artwork,” Peña says.

Peña wears turquoise earrings because it reminds him of his mother and the Yaqui Native American tribe.

To see some of Peña’s art, visit https://www.penagallery.com.