Slam poetry duo Mother Tongue gave a performance last Wednesday afternoon that left many teary-eyed, including the performers themselves.

Story by Brittany Wagner

Photos by Grayson Rosato

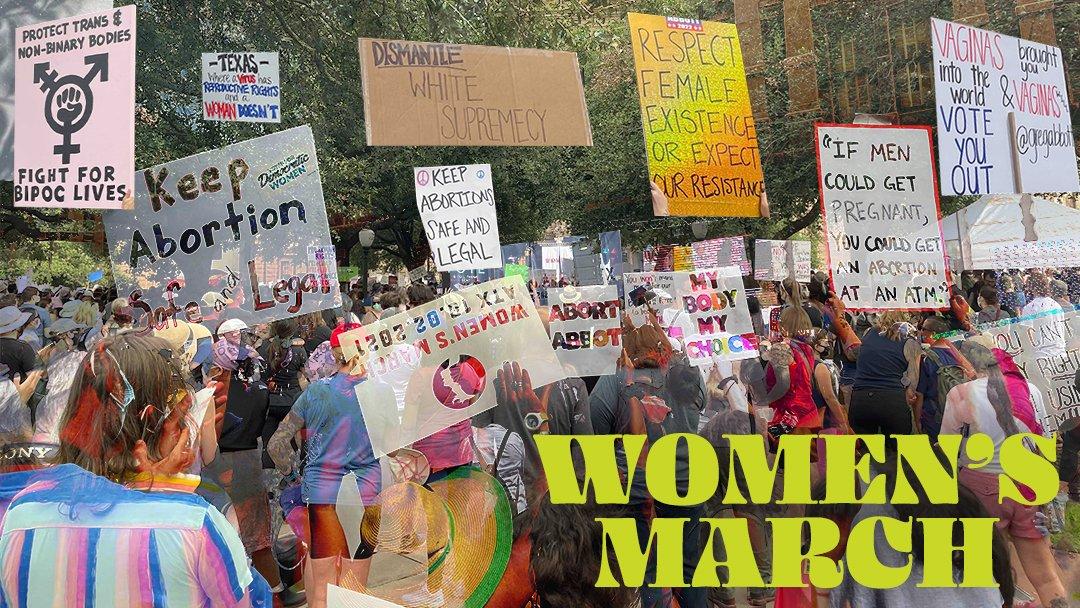

The duo consists of Dominique Christina and Rachel McKibbens. They were invited by the Gender and Sexuality Center, in co-sponsorship with Voices Against Violence, to celebrate National Young Women’s Day of Action.

The GSC has hosted the luncheon for at least the past ten years and spotlights people who bring activism to art, according to GSC director Liz Elsen. “I just think it’s an invaluable moment for those of us who are outside the cultural narrative to have a space to speak up and be in community with each other,” McKibbens says of the meaning of National Young Women’s Day of Action. “I absolutely want [the audience] to feel empowered and channel their inner witch.”

Mother Tongue is a slam poetry duo consisting of Dominique Christina and Rachel McKibbens.

The event began with Mario Alberto Ramirez, a member of the Indigenous International Youth Council, reading an indigenous acknowledgement written by Angela Lorena Vela Arce, who is part of NAIC and the Native American and Indigenous Studies Program at the University of Texas at Austin. Ramirez acknowledged that UT was built on stolen land and that colonialism is an ongoing structure.

Following the acknowledgment, Jasmine Bell, psychology senior and Spitshine poet, performed three of her own poems. “This first one is about anger,” Bell says before delivering some verses. Then she says, “The next two are about recovering from relationship violence and learning to love myself.”

McKibbens and Christina took the stage after Bell. “I’m just gonna get into it, all of my books are sad,” McKibbens says. “Sadness, it’s a gift! It’s a superpower!”

McKibbens started with a poem from her book, “blud,” describing her discovery of masturbation as the only way she survived the “endless winter” of her childhood. She then launched into a poem tracing her ancestry from Mexico, highlighting the shame she felt from not knowing how to speak Spanish. “I knew it was something mine, but not mine,” McKibbens says.

McKibbens is a nine-time National Poetry Slam team member.

In “Glutton,” she spoke about the pain she feels knowing her eldest son inherited schizophrenia from her. Within the verses she asked her son whether he has any friends, anyone he can talk to, and he answers “No, mom. I don’t have any friends.” At this point McKibbens began crying, and audience members teared up with her.

Christina’s poetry explored her relationship with her mother and the pain she endured growing up in a violent neighborhood, themes illustrated in the first poem she performed. “The murdered children I played with, the funerals that took all morning, the boys who murdered with indifference,” Christina says in her poetry.

Christina was raised in an intensely matriarchal family of proper Southern debutante ladies, and this upbringing created conflict because she says she “thought [she] was doing womanness incorrectly” by not behaving exactly like them. She delivered a poem dedicated to her mother and the differences between them.

During the Q&A session following the performance, the duo was asked to elaborate on McKibbens’ earlier statement that sadness is a superpower. “I think it’s what allows you to remain human,” Christina says. “It gives you a way to stay in your body and grieve.”

Christina holds five national poetry slam titles and is a writer for HBO’s series High Maintenance.

They were also asked what it was like to write their first poems and at what point they started to feel comfortable with poetry. “I don’t know that I’m comfortable, I’m just committed, it has saved my life,” Christina says. “I’ll do it over and over again in the acknowledgment of that, that it keeps me from being anything like my stepfather. It’s what keeps his body in the ground.”

McKibbens says there’s a necessary and healthy time lapse between trauma and the transformation of that trauma into art. “I think that young writers, particularly those that are in performance poetry, I’ve watched poetry that has encouraged them to bleed out in ways that I consider like re-traumatization,” McKibbens says.

French and humanities senior Barrett Smith attended the performance. “When I read about them I was like, ‘Oh my god they sound so cool.’ And they fucking were,” Smith says. “I liked what they were saying about living in the sadness. It allowed me to go to a [sad] place [in my mind] that I’ve been kind of avoiding [by using] margaritas and friends.”

Nikki Lopez, a history junior and an intern at the GSC, says she related to McKibbens’ verses about feeling ashamed that she couldn’t speak Spanish. “I feel like with some poetry it’s really good to see how people use their pain, but to actually relate to something, to hear it and see the pain in her face, I could definitely relate to that,” Lopez says. “I saw myself. And it stuck with me.”