For over a hundred years, marijuana has been demonized and dismissed by Texans. With more states reconsidering laws and stigmas about cannabis, is it possible for us to have a change of heart?

Story by Chad Lyle

Photos Courtesy of Mashable

Citizens of nine states now have the opportunity to start each day with a breakfast of eggs, bacon, and a marijuana-infused banana muffin. It should come as no surprise that if you live in Texas, only two of the aforementioned breakfast options are legally acceptable. But as cannabis-friendly places demonstrate mighty economic gains and public opinion shifts, a future might be in store for Texans and Mary Jane after all.

A year ago, Washington state surpassed one billion dollars in sales of marijuana alone. Colorado’s weed industry added 18,000 jobs to the state in 2015 and has contributed roughly 2.4 billion dollars to its economy. California’s pot market is expected to swell to 6.45 billion dollars in size within two years after retail sales go into effect next January. It sure doesn’t seem like the worst way to make a living. But will Texas, which prides itself on being business friendly, ever get over its short-sightedness and smell the money?

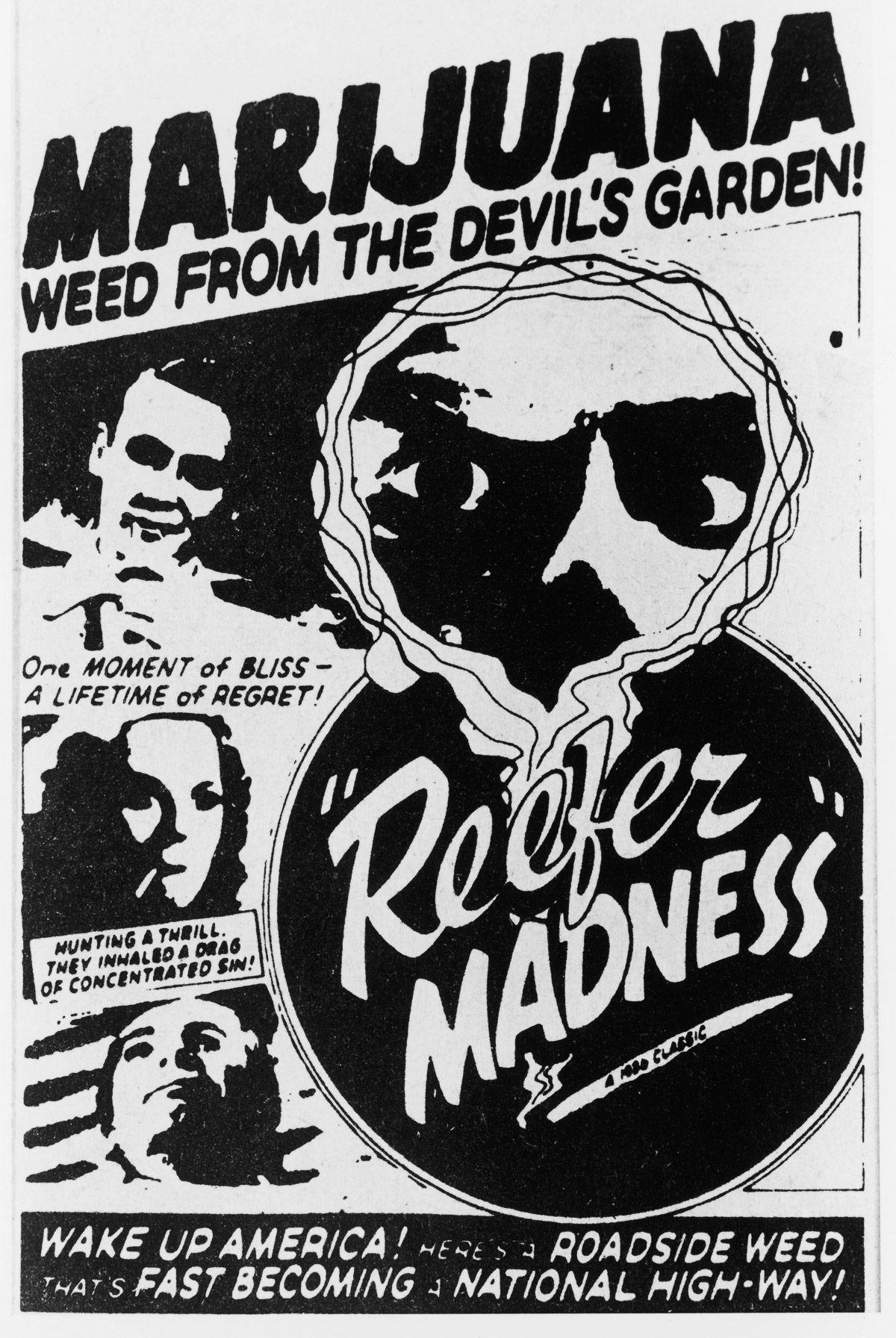

Cannabis wasn’t always the societal taboo that is is today, and Texas played a big part in getting it there. Colonial governments once championed the growth of hemp for utilitarian purposes such as making clothing and rope. During those times, hemp was officially traded as legal tender in Virginia, Pennsylvania and Maryland. Only at the outset of the 20th century did attitudes start to change. In 1915, El Paso became one of the first places in the U.S. to ban marijuana when a chief deputy of the Sheriff’s Department named Stanley Good wrote several articles for local newspapers tipping-off El Pasoans about the dangers of the substance, which he considered “the most deadly in its effect of any known drug.” His portrait of cannabis was to be expected of the time, however, with many unprincipled American journalists depicting Mexican immigrants as pot-crazy delinquents. The Texas state legislature officially banned marijuana in 1923, classifying it as a narcotic.

Until recently, the “Reefer Madness” paranoia that swept up Stanley Good and the Texas legislature was also the dominant lens through which the American people viewed marijuana. Thanks in part to states like Colorado that have demonstrated their ability to not only function but do spectacular business while operating in stoner paradise, the hysteria of old is slowly being replaced with pragmatism. 83 percent of Texans support the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes, while 53 percent support legalizing it outright, according to the Texas Tribune.

In this regard, Texan elected officials are out of step with the will of the people. Both senators, along with Governor Greg Abbott, stand opposed to most varieties of legalization, medicinal or otherwise. Despite the fact that a simple majority of Texas residents think they are ready to reap the benefits of a union between cannabis and good old American capitalism, our representatives disagree.

Lone Star hemp advocates have scored few victories. The only legislation that’s been passed statewide to cut against the grain of prohibition is the Texas Compassionate Use Act. It is not, as the name might suggest, exceedingly compassionate. Passed in 2015 (100 years after Stanley Good rode the devil’s harvest out of El Paso), the TCUA permits the sale of a distinct variety of cannabis oil for epilepsy patients. It certainly marks the first time Texans have been able to produce or market cannabis for any reason, but detractors of the law contend that the modest amounts of THC and CBD allowed on the market are too small to be helpful.

Though the Texas Compassionate Use Act starts and ends the list of substantive victories for Texans who like pot, some recent activity in the state legislature might be a ray of hope for the future. A more traditional medical marijuana bill was written by Congressman Eddie Lucio, featuring 77 co-authors (out of 150 members of the Texas House), both Democrats and Republicans alike. Meanwhile, Rep. Joe Moody proposed a bill that would take criminal penalties out of the equation for people caught with less than an ounce of marijuana. According to Moody’s bill, possession would still call for a 250 dollar fine, but would no longer warrant a criminal record entry. 41 Democrats and Republicans co-authored Moody’s bill. Yet neither piece of legislation landed on the House floor in time for a vote.

So what about the future? A California-sized economic boom is nothing to turn a blind eye to, and neither are Colorado’s 18,000 jobs. If Texans are ready to make the argument, all of the evidence is at their disposal. The Texas Legislature doesn’t meet again until 2019, but when it does, Texans who want to see more bills like Moody’s and Lucio’s should call their representatives and make sure laws like that are being drafted and pursued. If not, voting out incumbents in favor of more marijuana-friendly candidates couldn’t hurt. Support from state politicians is clearly building, even if the most prominent of them still bristle at the subject. The old guard may claim to fear the uninhibited influence of a narcotic on public safety, but the mortality risk associated with marijuana is about 114 times less than that of alcohol. The signs point to progress, but the question is how quickly Texas and Mary Jane will get to know one another.