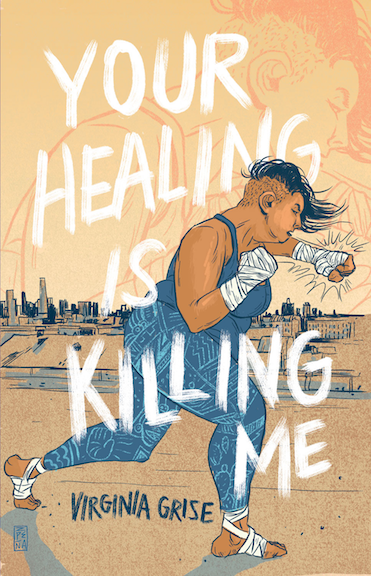

Virginia Grise’s performance manifesto “Your Healing is Killing Me,” explores her identity as a queer Latinx artist and activist in Texas through the lense of her personal socioeconomic and cultural experience. Her powerful messages create broader statements about the lives of both women of color and those who identify within the LGBTQ community in Texas.

Story by Sage Foster

Three actors took the stage of the grayDUCK gallery in East Austin on Oct. 14 to present Grise’s piece. Each actor took turns speaking lines from the manifesto, delivering a narrative that was creative, personal and autobiographical. “Your Healing is Killing Me” is Grise’s fourth published piece in which she explores discrimination based on race, gender, sexual orientation and social class.

Though Grise’s manifesto encompasses a vast range of topics, one of the primary focuses is her difficulty in obtaining health care. She writes of her transition from frequenting “curanderas,” practitioners of Native folk healing, with her mother to seeking traditional medical healthcare as an adult. Prior to the Affordable Care Act, Grise was unable to afford insurance and wasn’t eligible for Medicaid because her income was slightly above the line for qualification. A lack of healthcare options forced her to engage in risky behaviors, one of which included visiting a black market doctor for her severe eczema.

When Grise was finally able to seek help from medical professionals, she found that they were either unable to identify the cause of her symptoms or medicated her in a way that treated the symptoms of her eczema but not the cause. Grise argues that this incompetency can be explained by the idea that “doctors operate inside of a system that doesn’t really care about your health,” holding that the United States’ healthcare system functions in an exclusionary way in which only those with certain socioeconomic privileges are able reap its benefits. She cites this dynamic as one of many instances that occurs when government policy is designed to benefit only a specific margin of society.

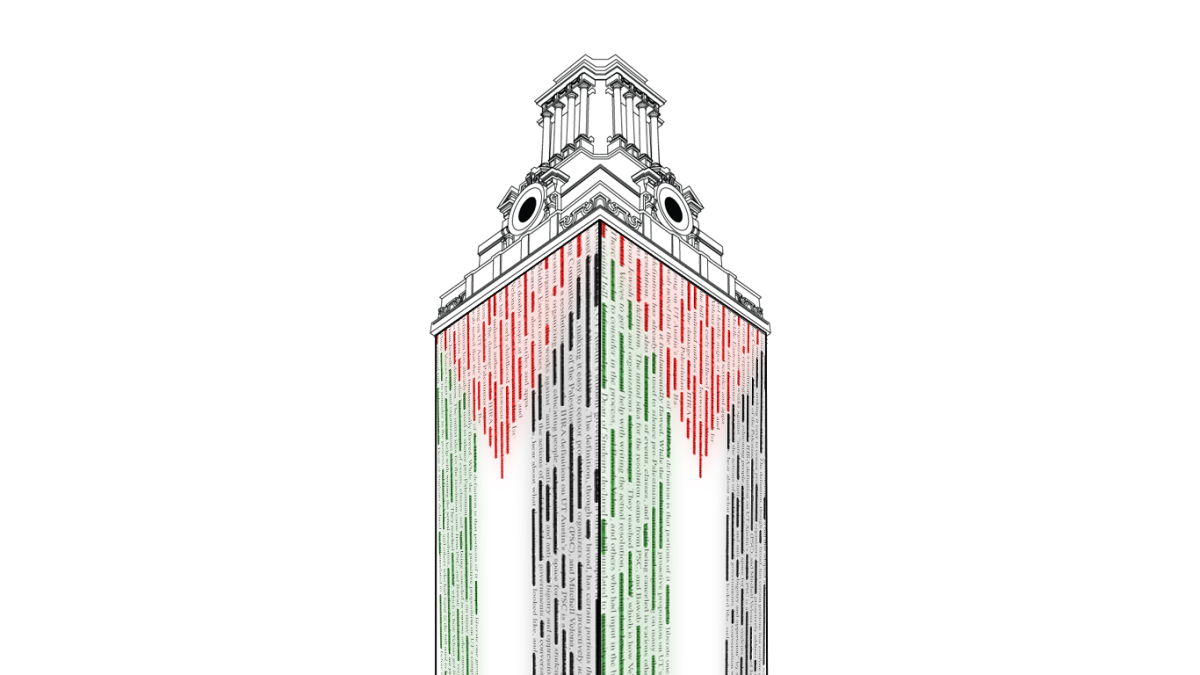

Photo courtesy of Zeke Peña

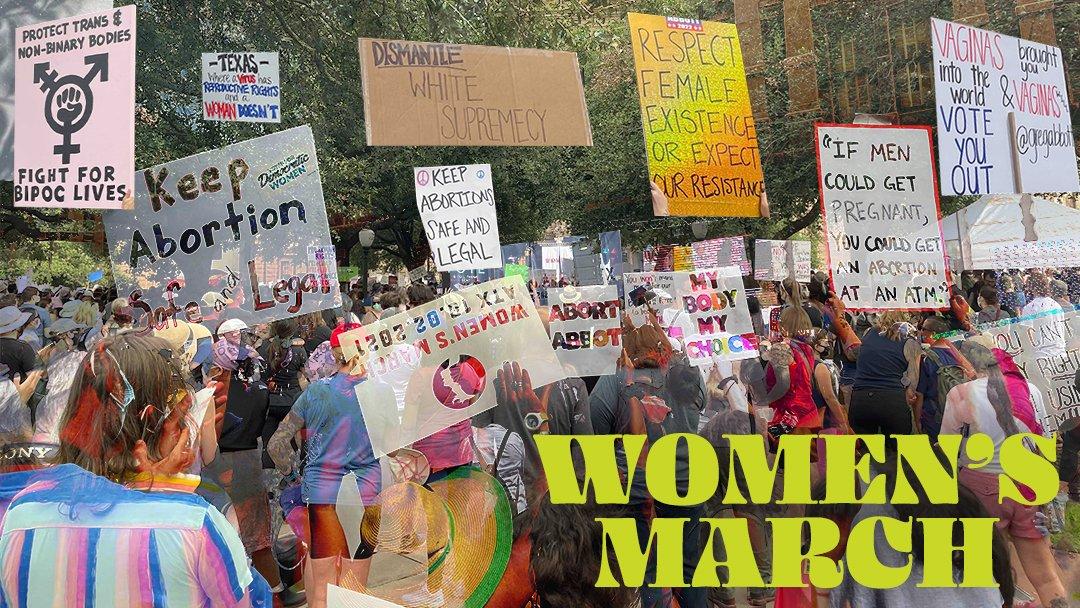

Grise’s piece also describes her experience as an artistic activist for the Latinx community in various towns in Texas, including Austin. Through both written works and physical activism, Grise fights against institutions and dynamics that act as sources of oppression for herself and others in her community. The manifesto lists factors including white supremacy, underrepresentation, lack of political imagination in a two-party system, rigid gender roles and the absence of free healthcare, each of which she argues is “killing” her.

New Austin resident Judd Farris says this aspect of the performance really stood out to him, noting Grise’s focus on “the toll that activism takes on people, particularly women of color in terms of having to fight for basic rights. “They are fighting for things that are unconditional for so many people,” Farris says. This emphasis on the harm caused by both structural and social flaws is central to Grise’s work.

Grise also speaks of her role models in the Latinx empowerment movement, including the Chicano writer and revolutionary Raúl Salinas. Soon after his release from prison, in which he engaged in a strike for incarceration reform, Salinas opened a bookstore in Austin called Resistencia, a place Grise describes as somewhere that once felt like her home. Though Salinas has since passed away, the small East Austin bookstore remains open.

The focus on Grise’s revolutionary heroes in the performance manifesto leads into a dialogue about the prisons, both literal and metaphorical, from which oppressed groups seek refuge. In the narration of her own efforts to obtain physical and emotional freedom, she projects her message to disenfranchised groups in the United States at large.

Through an anecdotal story about her experience visiting a university, Grise discusses how students of color often feel unheard by their professors who, despite their high levels of education, can’t fully understand their students’ experiences. Through this phenomenon, she theorizes that even spaces that appear safe for women of color are not always so. “I thought it rang true when she spoke about students of color at universities that weren’t being heard by their professors,” University of Texas at Austin government and economics junior Ida Kamali says. “A lot of people of color, especially women of color, can’t find a place where they can feel physically or mentally safe, especially in predominantly white institutions. I can identify with this, as can many of my friends, as many aspects of universities cater to white students.”

This discussion continues Grise’s argument that a vast majority of America’s institutions don’t exist to serve all members of society. “An entire industry has been created around the idea of self-care without actually naming what is putting us at harm,” one of the actors read towards the end of the manifesto. With this poignant statement, Grise gestures to the difficulty of attempted healing in a sociopolitical system that is often the root of, not the remedy to, one’s harm.

Austinite Chelsea Rodriguez says she was struck by the piece’s emphasis on “the multi-racial undertones and the lack of cultural sensitivity from all sorts of liberals.” Praising Grise’s work, Rodriguez says, “it was so powerful, so genuine, just words you need to hear as an emerging person in the world.”

Sebastian • Nov 5, 2017 at 6:54 am

I can truly say I enjoyed reading this article.