Artistic duo Billi London-Gray and Daniel Bernard Gray bring Austin a strong message about the meaning of truth and power in 2017 with their multimedia exhibit “BELIEVE ME,” on display in the grayDUCK gallery through Oct. 29.

Story by Sage Foster

Photos by Grayson Rosato

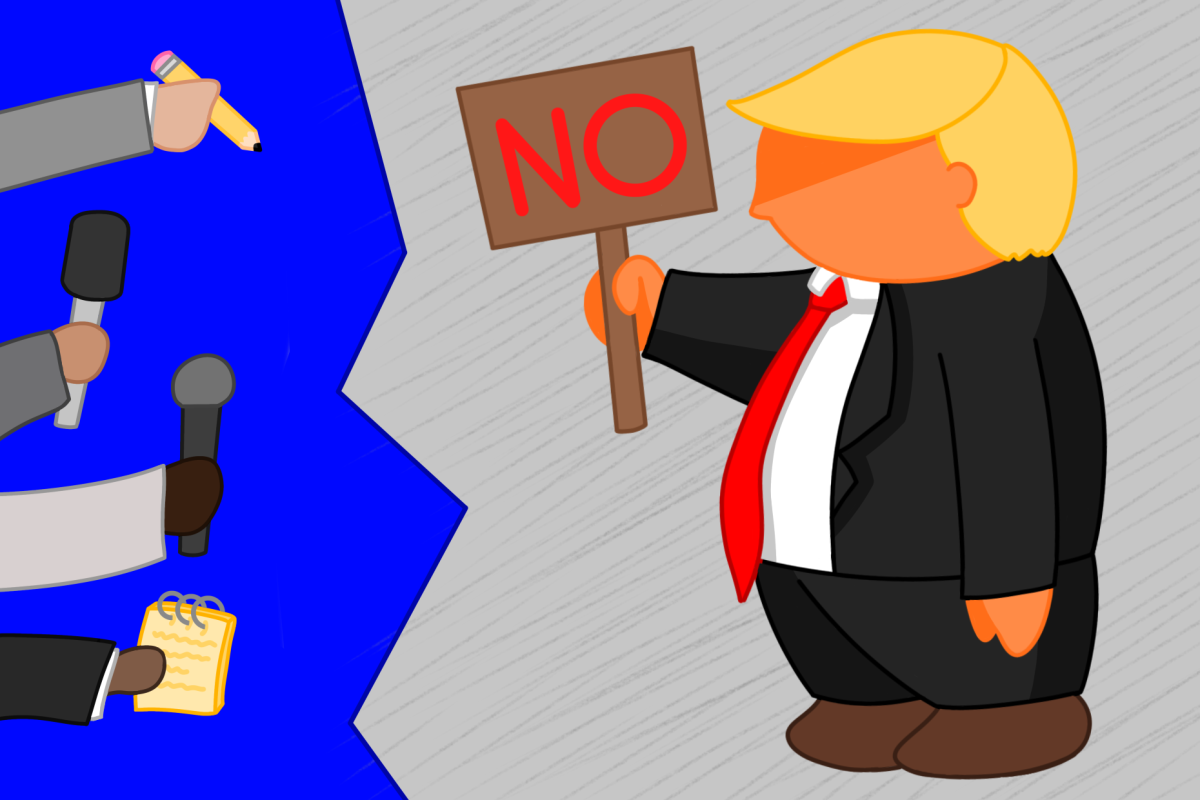

The first piece that catches the eye when you enter the exhibit is a white wall, upon which a introductory message to the reader is scrawled in faint red print. “Believe me, I know,” it says. “Boy, do I know.” A satirical invitation follows as the writer begs the reader to believe them because they are a “straight shooter” who has “nothing to hide” despite a lack of supporting evidence for their arguments, which the writer excuses with the assurance that they have no reason to lie. Ironically, these requests for blind trust are paralleled with persistent, anti-establishment dialogue that urges the reader to not believe what the “biased” media tells them, because “they want all the power.” The media has an agenda, the writer insists. “They’re insiders!”As the writer continues, addressing the readers as “folks” and praising them as “honest people, hard-working people who can figure this stuff out,” it becomes evident that the artists are parroting rhetoric used by President Donald Trump to address the American people.

The series of small, handmade books welcome the visitor into the exhibit with words, sketches and photographs that question the meaning of truth.

This wall of manipulative contradictions and populist appeals serves as the perfect opening for the artists’ exhibit, which combines Bernard Gray’s exploration of varying definitions of truth and reality with London-Gray’s focus on established systems and power dynamics. The writing on the wall is the first element that reveals the Grays’ exhibit as a simultaneously subtle and distinct outcry against Trump’s America. As gallery visitor Raúl Gonzalez points out, however, Trump isn’t the artists’ sole conceptual focus. “What comes to mind is the global, for lack of a better term, view of politics which is Trump being the problem, Trump being the cause, when really he’s just a manifestation of what’s really happening underneath it all,” Gonzalez says. This gestures to the finger-pointing impulse felt by many politically active citizens who have a desire to change but no notion of where to begin, a phenomenon that is only worsened as truth becomes increasingly distorted and muddled.

Bernard Gray’s series “Shrieking Violins” makes use of materials including soot, lacquer and aluminium silicate.

The next aspect of the exhibit is a collection of small, handmade books that visitors are permitted to flip through. Many of the books appear absurd — “The Sordid Truth About Cats,” for example, drily informs the reader of facts about cats, including the assertions that cats invented brunch, are the Illuminati and were the first animals in space. Other books have no words and are merely a collection of arrows and other signs on recycled plastic material. In the book called “The Pocket of Protective Incantations,” every page lists a different way to say no. Another book lists various medical complaints that describe bodily illness, pain and unrest. Certain pages can’t help but seem politically angled; some say “left side more affected than the right,” or “intermittent pain radiating left side.”

The colorful, recycled quality of these books is part of a stylistic theme that is present throughout the exhibit.

The final book in the row consists of various photos of scenes or people accompanied by Post-it notes upon which messages are written. Messages range from seemingly meaningless phrases like “emergency tampons” to political ones such as “our nation stands for due process,” or “exposure to goodwill doesn’t pay the mortgage.” The books and their content further the Grays’ artistic statement about the ambiguity of truth, lies and beliefs, particularly those determined by whom the facts come from. “The theme itself is very on point politically and with where we find ourselves historically,” Gonzalez says.

The artists’ creative transformation of seemingly ordinary materials into art is a large element of their work.

There are two videos projected throughout the entirety of the exhibit, both of which depict an abstract array of colors. While one is relatively still, albeit with slight camera movements, the other gives the viewer the illusion of falling endlessly amid billowing fabrics. Large pieces of painted rubber are also mounted near the videos, several of which are composed of the same earthy color palette as the videos, blended and merging into one another. These are accompanied by a plethora of other abstract recycled pieces, including wiry, hay-like material that covers one corner of the room. “I found the repurposing of lots of different types of material interesting,” says gallery visitor Mary Gonzalez. “It’s taking trash things that just kind of take up space and finding a way to make them something beautiful and also meaningful.”

London-Gray’s acrylic and dirt heat drawings on rubber evoke ideas about femininity and sexuality.

While the exhibit is rich with a wide variety of pieces, some feel the emotional commentary on modern American existence is particularly poignant. The rubber motif continues with a trio of three large paintings that depict abstract, colorful shapes resembling breasts and fruit that mimic ovaries. “To me, these paintings are a critique of Trump’s sexist attitude toward women and how he has ultimately taken power away from them,” University of Texas English junior Michael Jones says. Another particularly relevant and captivating piece is “Sorrow, But Not Contrition,” which is composed of many different medias, including an American flag, shelves from the presidential library and crushed concrete. The flag, covered in dust and rubble, faces the wall of the gallery rather than the viewer. “The placement of this piece is highly noteworthy,” says Jones. “It says we as Americans are facing away from what the flag symbolizes and as a result, the flag now resembles a dying country and a disrupted society. It stands for something that has been used to divide us.”

London-Gray’s “The True Meaning of Covfefe” brings an ironically upbeat sentiment to the end of the exhibit.

Despite the wide variety of mediums and subject matter, the message of the artists seems to resonate with every gallery visitor. Trump’s election appears to have acted as a catalyst for the work and remains a highly relevant discussion point for questions about truth and the examination of power dynamics. However, the artists express these conceptual queries through a broader lense that examines the underlying factors that allowed for Trump’s election and the birth of our current sociopolitical climate, the somber quality of which echoes throughout the gallery. “It’s like we’re losing something,” Raúl Gonzalez says. “We’re just at a point that we can’t control and we’re all grieving over it.”