On Nov. 7, Travis County will hold a general election vote for an Austin Independent School District (AISD) bond along with a county municipal bond and seven other constitutional amendments.

Story by Will Kosinski

Illustrations by Ryan Hicks

University of Texas at Austin students can vote at the Flawn Academic Center, but for additional details about when and where to vote on Nov. 7, click here.

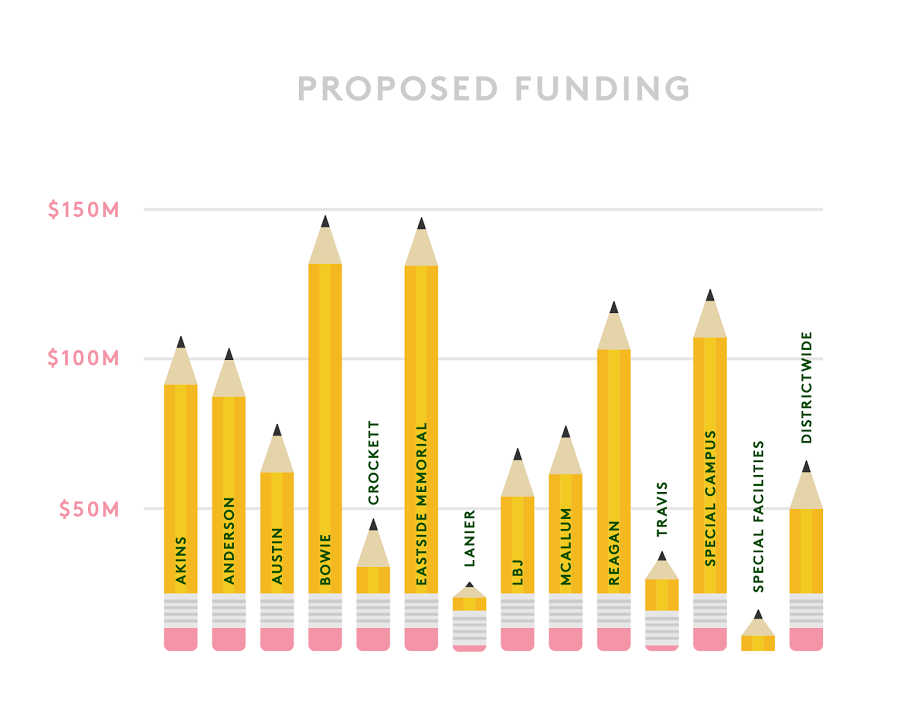

The $1.05 billion AISD bond will finance plans to build new schools and repair old ones that are becoming unfit for learning. However, many worry that the bond is structured to favor the affluent, majority white schools in the district while underinvesting in low-income, majority African American and Hispanic schools. Opponents say the bond will lead to a resurgence of inequity, inequality and segregation in Austin, a city that historically struggled to integrate.

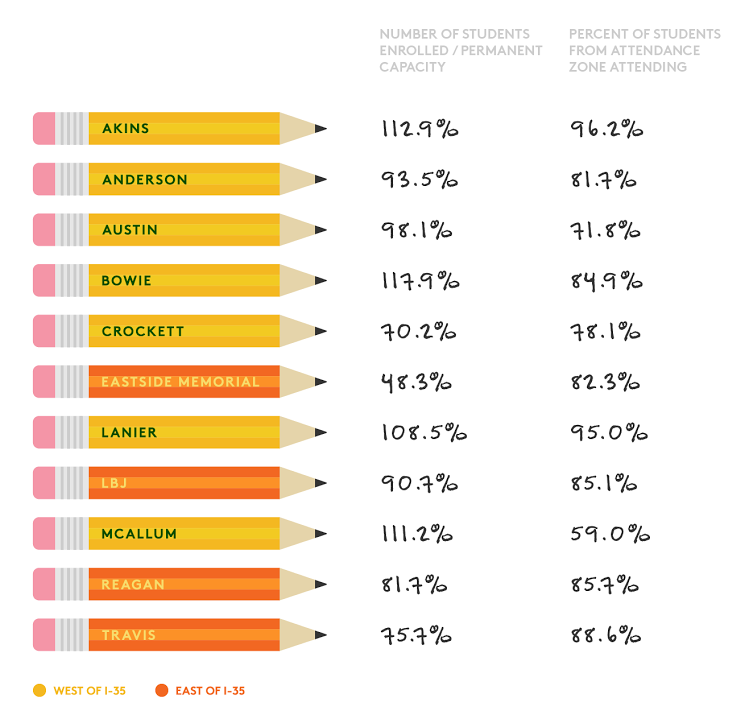

There is an achievement gap that many, including AISD itself, acknowledge within the city. Enrollment disparities contribute to the gap because lower enrollment reduces funding. In addition, many speculate that this student performance gap is due to a lack of financial resources for schools in lower income areas, a concern the city is attempting to address with this bond.

On Oct. 11, the East Austin Coalition for Quality Education and Equity hosted a panel to discuss the bond and address the concerns of inequity. The general consensus among speakers recognized the consequences of the bond failing and was summarized by AISD School Board Trustee of District 2 Ted Gordon. “Not enough equity was put in the bond,” Gordon says.

Notably, a majority of the panelists condemn the fact that an inappropriate amount of money will be distributed between the areas west and east of I-35, the city’s permanent reminder of racial segregation. Former District 6 AISD School Board Trustee Paul Saldaña explains that about ⅔ of the bond monies are going to schools in west Austin. Peggy Vasquez, representative of Save East Austin Schools (SEAS) says, “Only 35 percent of bond monies are going to Title 1 low income schools. 75 percent of Austin ISD students are minorities who are typically in Title 1 schools.”

According to Jacob Reach, the assistant to the AISD Superintendent, these figures are misleading. “To make the claim that all of these students are in Title 1 schools is just plain false,” Reach says. “Those students are across all of our schools.” Whether or not a school can be defined as a Title 1 low-income school depends on at least 40 percent of low-income students qualifying for free or reduced lunch within attendance boundaries, which is a set zone around the school where students should attend. Some students attend private, charter or public schools via transfer outside of their attendance zone while still meeting the boundary they live within. Reach states that 44 percent (not 35 percent, as stated by SEAS) of the bond monies would go to Title 1 schools. He also recognizes that schools without Title 1 status may still house students in need.

Rosedale School, an elementary school for students with special needs, is not considered a Title 1 school because it lacks an attendance boundary. Nonetheless, these students have high needs. Similarly, Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders is not a Title 1 school, yet about 60 percent of its students are economically disadvantaged.

Closing schools in east Austin is another large concern among the panelists. Gordon explained that if the bond passes, some neighborhoods in the eastern part of the district could be left without schools. This may strain already overcrowded schools that would struggle to serve the new students coming from under-performing schools.

The concern over schools closing due to the bond is another misconception. The closing of schools is probable whether or not the bond passes, according to Reach. “This is really about how we could, instead of fixing up three schools that have low enrollment and may not have the same efficiencies as some of our other schools, bring them together and create a brand new school for them,” Reach says.

Low enrollment is a problem facing many schools in Austin. Enrollment is part of how AISD allocates its budget, so when the number of students attending a school falls, money for teachers and resources fall. This results in cuts to faculty and programs.

Victor Tovar, a parent, former teacher and activist of AISD schools, says, “Affordable housing is the biggest reason why kids leave east Austin schools, because they can’t find a place to live.” Reach agrees and says he has found similar results from demographic analysis.

A flyer created by AISD to promote the bond says that the bond can finance AISD schools without an increase in property tax rates, presumably in an effort to swing voters with financial reasons. This is important to the residents of a city where property values increase exponentially.

However, the claim is still misleading. Whether the bond passes or fails, the nominal amount of property taxes are going to continue to increase in Austin where, in the past five years, the average property tax bill residents pay has risen 21 percent. Financing for the bond comes from the expectation that the continual increase in property values and nominal taxes could pay for interest on the bond and eliminate the need for a rate increase.

Whether the bond passes or fails, AISD can expect more low-income families to leave the city as they cannot pay for increasing nominal property taxes. For those who can still afford to live in the city, President of Greater Austin Black Chamber of Commerce Tam Hawkins says, “People don’t have a problem paying more in taxes, they have a problem with the return of those taxes.”

More and more parents are deciding to take their kids out of AISD’s public schools and put them in charter schools because they are producing better results. “Charter schools say that they are trying to or need to serve low-income students of color who aren’t graduating from high school,” Tovar says. “But what charter schools end up doing is working with kids who don’t have as high of needs, who don’t have behavioral issues. [They’re] creating a fabricated environment where students that are likely to succeed anyways are going to these schools.”

According to Tovar, students with the most need either can’t afford an application or adhere to the charter school’s strict policies. They then return to the public schools, further enabling charter schools to boast about their success.

Vasquez and Saldaña, who are fighting against the bond on grounds that it is inequitable, have ties to charter schools. “Peggy Vasquez runs a show called Hispanics Today Live, and it is underwritten by Southwest Key,” Tovar says. “Southwest Key has a charter school here in town called East Austin Prep. Paul Saldaña, in the spring of 2011, advocated to have Southwest Key Charter Schools and East Austin Prep, take over Eastside Memorial High School.” Tovar alludes that charter school affiliations could riddle their stance against the bond with ulterior motives.

Equity and performance can improve whether the bond passes or fails through increased access to affordable housing. According to Tovar, the Eastside Memorial Vertical Team has had rallies for affordable housing co-located on AISD lots. Similarly, AISD is in commitment with the city of Austin on CodeNEXT, the initiative to revise the land code and effectively address growing issues with Austin’s population shifts. Both of these efforts can keep families in schools to prevent under-enrollment and slow gentrification.

There is a divide amongst east Austin parents and educators about the bond. The Parent-Teacher Associations of Eastside Memorial High School, Martin Middle School and Govalle Elementary School support the bond even though many east Austin parents form an opposition.

One such parent in opposition is Angela Benavides Garza, a mother of two sons born and raised in Austin. One of her sons, Joshua Cardenas, graduated from McCallan High School about 10 years ago.“[Joshua] was four grade levels behind on reading,” Garza says. “We wanted to make sure he wouldn’t fall farther behind.” She worked tirelessly to ensure her son got the education he needed by finding support for him and moving schools. She wants kids in east Austin to have access and equity, which she believes the bond does not sufficiently provide.

For Garza, community engagement is key to improving student lives and this starts with parents.“Turn off the televisions and get engaged. We need to be proactive in making sure our kids can succeed,” Garza says. “This includes discussion and voting on this bond.”