In order to comprehend the exclusion and lack of influence given to indigenous peoples, one has to understand who is allowed to qualify as Native.

Story by Kateri David

Illustration by Annette Hui

I realized I was Cherokee the same way I came to understand myself as Polish: my parents told me and, gradually, I came to see my appearance as a consequence of descent. I felt steeped in a shared tribal history whenever I attended the Cherokee National Holiday powwows in Talequah, Oklahoma. I saw myself reflected in my grandmother’s ochre skin and broad nose.

Years later, as I was filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), I discovered that my Cherokee racial identity – unlike my Polish ties – was quantified. In order to be recognized as Native American, I was required to submit proof of tribal enrollment. Issued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, proof comes in the form of a non-laminated slip of paper resembling a social security card that lists one’s name, birthdate and “exact” percentage of their Cherokee blood, down to three decimal points.

Some say this system of constructing “Indian-ness” or tribal enrollment seems needlessly precise. Although federally recognized Native American tribes operate under a certain degree of autonomy, most indigenous people are still bound by blood quantum – a series of laws set by the federal government and former colonies to restrict tribal membership. As tribe members have children with non-members through each passing generation, the bloodline shifts and reduces tribal membership in turn.

When reflecting on Indigenous People’s Day, it is time to recognize the harm enacted by blood quantum law on identity and how it racializes the political. As David Wilkins says in “American Indian Politics and the American Political System,” “American Indian tribes are nations, not minorities.”

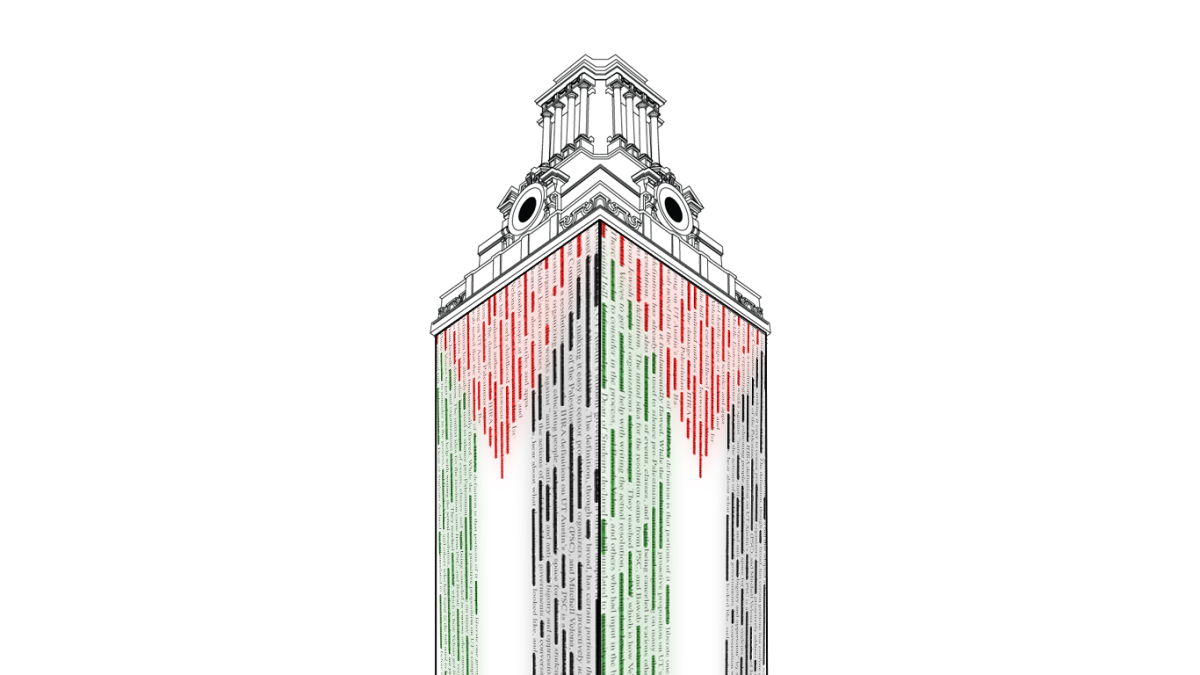

At the University of Texas at Austin, only 0.2% of the current student body is composed of self-identifying Native Americans, a virtually invisible group. However, making sense of our lack of influence on campus and in the nation (2% of the total population) requires an understanding of who is allowed to qualify as Native.

Although blood quantum is an artificial system created under settler colonialism and , (no North American tribe used blood quantum prior to the federal government’s legislation, most tribes in the United States have hauled this practice into the present day, albeit with slight modifications from tribe to tribe.

To enroll as a member of the Apache, one of the largest tribes in Texas, one would have to possess at least ⅛ degree of total Indian blood. For the Cherokee and Comanche tribes, the requirements are less stringent, asking only for proof of descent from ancestors listed on the Dawes Rolls.

Tribes in favor of blood quantum laws argue for their necessity in maintaining the tribe’s racial integrity. They “look upon those blood quantum as a way to preserve an already existing closed community that’s very close and … usually very culturally connected,” says Elizabeth Rule, a doctoral candidate at Brown University specializing in Native American studies.

On the other hand, UT anthropology professor Circe Strum argues that the conflation of ancestry with race leads to a hyper-focus on racial integrity that excludes certain groups. In “Race, Sovereignty, and Civil Rights: Understanding the Cherokee Freedmen Controversy,” Strum details the plight of the descendants of African Cherokee slaves once held by Cherokee slave owners. Since the Cherokee tribe does not require blood minimums, citizens can range from “full-bloods” to “1/4096.”

Though the policy of lineal descent has cultivated a vibrant, diverse community, it has also generated racial insecurities. Aware of how the “broader public racializes their status as an indigenous nation,” the Cherokee consistently deny citizenship to Cherokee freedmen on the basis of the racist “one-drop rule,” a regulation that classifies anyone with African ancestors as black and nothing else. Partially due to heavy colonial influence and imposed regulations, Cherokees fear that “racial dilution may threaten their political recognition and eventually their sovereignty,” Strum says.

For generations, and against their most valiant efforts, tribes across the North American continent have witnessed the disappearance of their people, land and culture. They have been gouged by genocide and relocation time and again. Now, we are faced with a mute but equally sinister violence in the form of blood quantum laws.

The hope is that, “over time, Indians would literally breed themselves out and rid the federal government of their legal duties to uphold treaty obligations,” Rule says. Indigenous People’s Day is about resistance, with many Natives being left with the choice of buying into a system and dying out, or rising up against it.