The past is a tricky thing with a rather odd habit of manifesting itself in the present. When you think you’ve outrun it, it sneaks up behind you and spins you in circles until you’re too dizzy to keep running.

Story by Mia Uhunmwuangho

Photos by Hannah Vickers

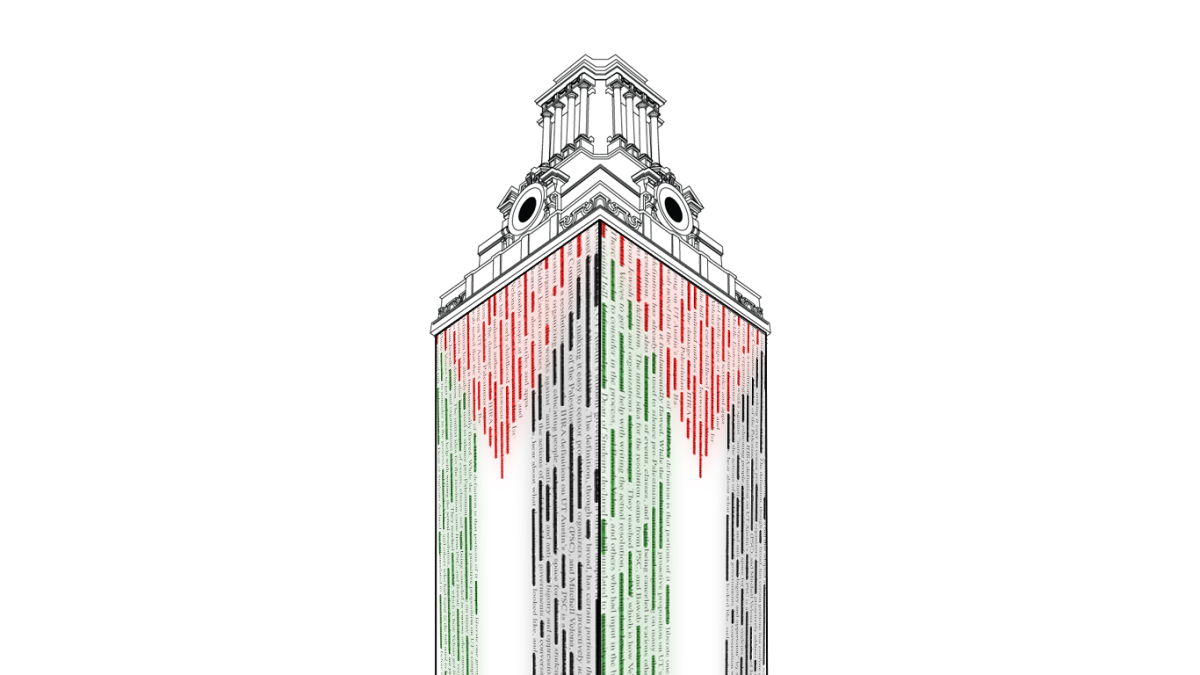

Black students at the University of Texas at Austin are running this race with the past, and the dizziness reaches its peak every February during Black History Month. They’re told, “Wow, look how far you’ve run! Forget about those rocks that tripped you; the worst is over!” But black students realize they’re tripping over the same rocks, just in different positions. In other words, the issues and struggles concerning black students haven’t disappeared — they’ve simply evolved. Segregation is no longer an issue, but black students now deal with the scrutiny of being the only black person in a classroom. The court case for affirmative action may be over, but black students now hear statements like, “You’re only here because you’re black.”

These issues, combined with other factors, are why up to 25 percent of black students get dizzy, stop running the race and drop out of UT before graduation.

To help student escape the runaround, UT’s Black President Leadership Council organized an event called The State of Black UT. The event was an open forum featuring guest speakers and breakout sessions where students and faculty could raise questions and concerns about issues facing the black community on campus. The key issue was about retention and keeping black college students in school.

“A common theme I’ve seen lately is the lack of retention,” Adrianna Kelsey, director of the Black Presidents Leadership Council, says. “It’s not just because of education and not being able to keep up with the work. It’s mental, financial and social.”

While low retention rates aren’t unique to the black community, they hit black students harder because of the black population’s small numbers on campus. Black students have never reached a population of more than 3,000 students on campus, so when 25 percent of students drop out, it has a large impact. “Just based on the numbers, this has a negative effect on black people,” Kelsey says.

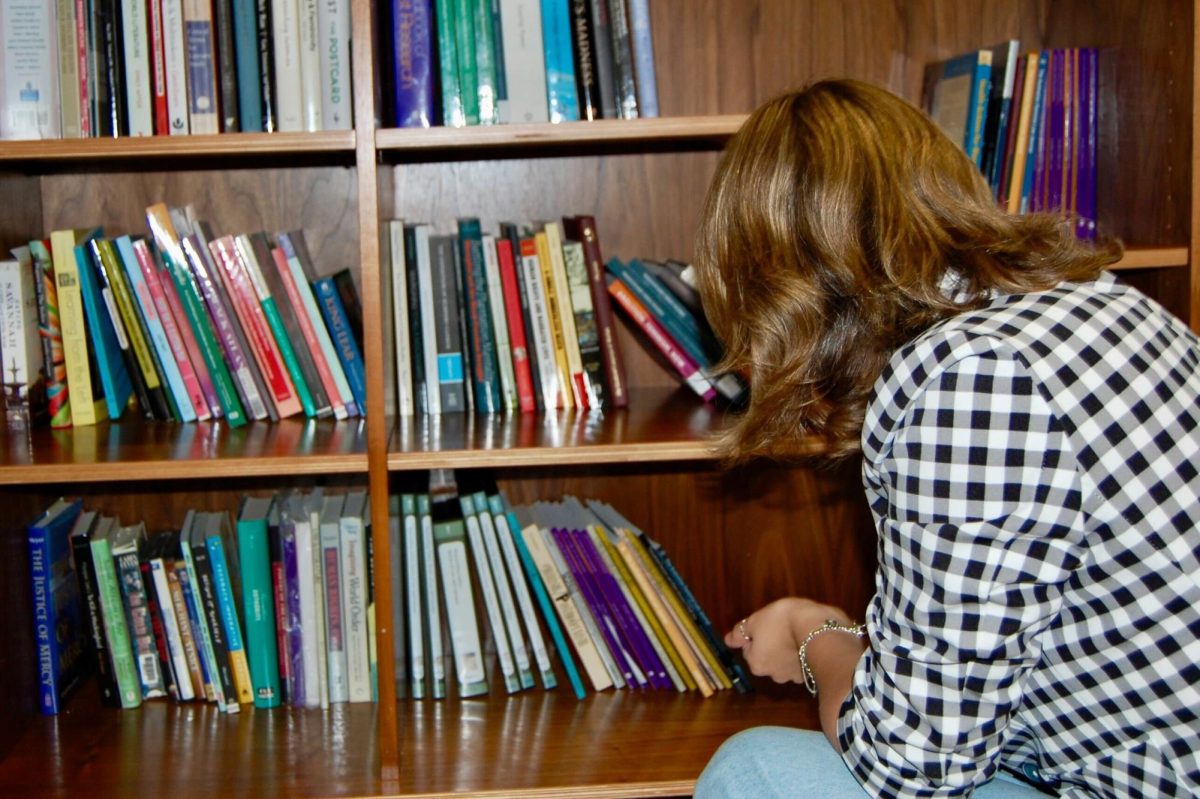

“The State of Black UT” was not only a means of discussing retention — it was an open forum where guests could share their experiences. As students shared their personal encounters with racism on campus, family problems and financial distress, there was an underlying theme. When black students face these issues, they aren’t aware of the resources available to help to them, so they drop out.

But black students aren’t just choosing to be ignorant of resources. Chelsea Jones, former president of the Black Presidents Leadership Council, says that black students are unaware of the available resources because they feel so disconnected from campus. “Black people are underrepresented on campus, particularly in student government,” Jones says. “It’s hard to ask for help when no one around you looks like you. It makes you feel alone.”

While there is help available, a lot of the resources are contingent upon how well black students perform academically. These resources have been changing over the past few years, as money is being invested and divested based on retention and graduation rates. Tiffany Tills, director of the Longhorn Link Program that specializes in retention, says that this not only affects current students, but prospective students as well. “When we were looking at the data, you saw the dips in 2013 and 2014,” Till says. “Those were the years where the university kind of divested, meaning they took away a lot of the scholarship money for incoming freshmen. They weren’t recruiting them with scholarship dollars. But then, the numbers got so low, alarming low, that they had to go back and rethink the strategy.” The rethinking and reinvesting led to scholarships like the Texas Advance and to special programs like the University Leadership Network and Gateway Scholars.

UT’s reinvestment in its black students has opened several doors, although there is still some progress that needs to be made in the black community. To help brainstorm ideas to solve the issue of retention, the Black Student Leadership Council had students break up into groups to discuss various solutions. The majority agreed that the primary solution is to develop a mentorship program where upperclassmen work with underclassmen. By working with someone who knows what it feels like to be the only black person in a chemistry class, to be ridiculed for dark skin and natural hair or to be stereotyped as the thuggish black athlete, students will feel encouraged to press forward.

The solutions and mentorship programs may not happen overnight, but now students are informed of the resources available to them, as well as the issues that the black community faces. “People are aware and want to become more aware,” Kelsey says. “We’ve seen more students getting involved.”

The state of black UT is one that is growing and constantly changing, but progress is always being made. And this Black History Month, as we celebrate the likes of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, don’t forget about the black students that are running the race and making a difference right here on campus.

#BlackStudentsMatter.

Note: Statements in this article reflect the opinions of the writer.