Much has been said about the Internet age, with many-a-gripe about how technology has removed the personality from everyday life. But with 191 million users, including 87 million paying customers, Spotify has mastered the art of crafting a unique human experience through robotic means.

Story by Carys Anderson

Photo courtesy of Spotify

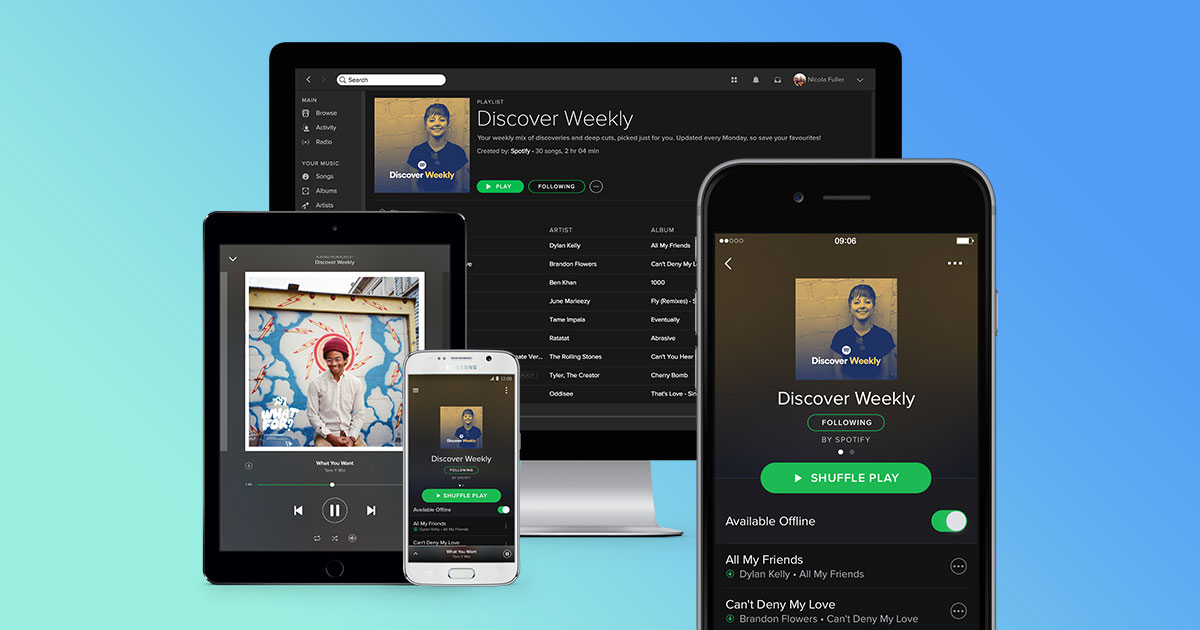

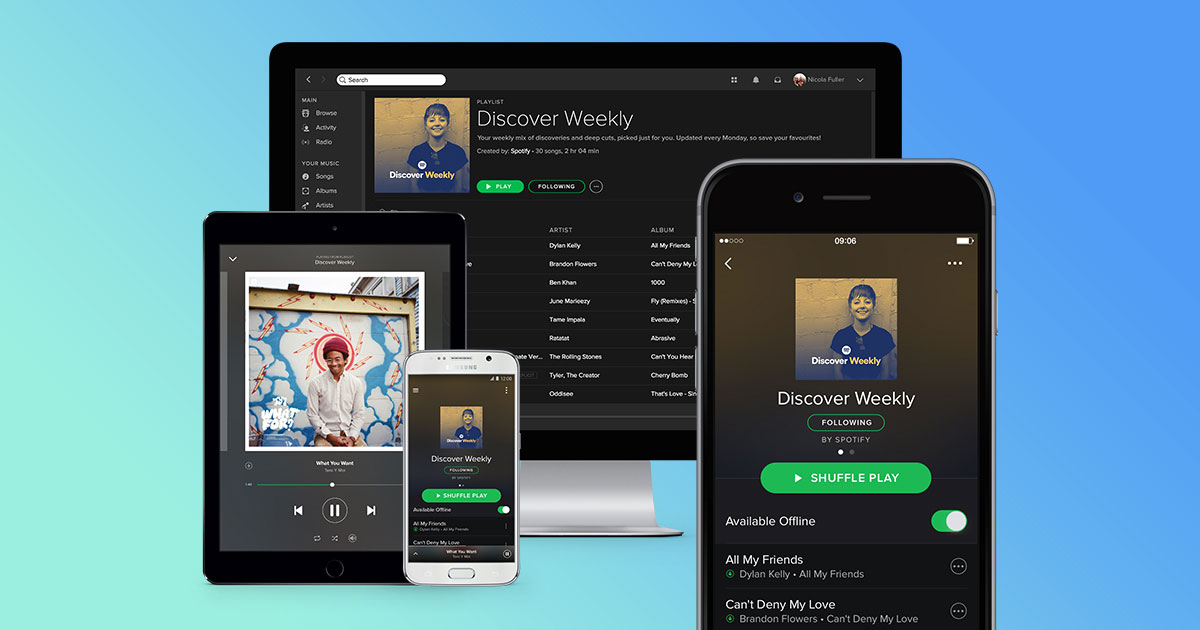

Open Spotify and the first thing you see is a page full of playlists dedicated to every possible mood. Two pages down the dashboard exists a page of playlists that were “Made For You.”

From vinyl to CDs to the first iPods, the digital revolution first simply changed the format on which people listened to music. Nowadays, however, the streaming giant Spotify has entered the world of curation, to enormous success.

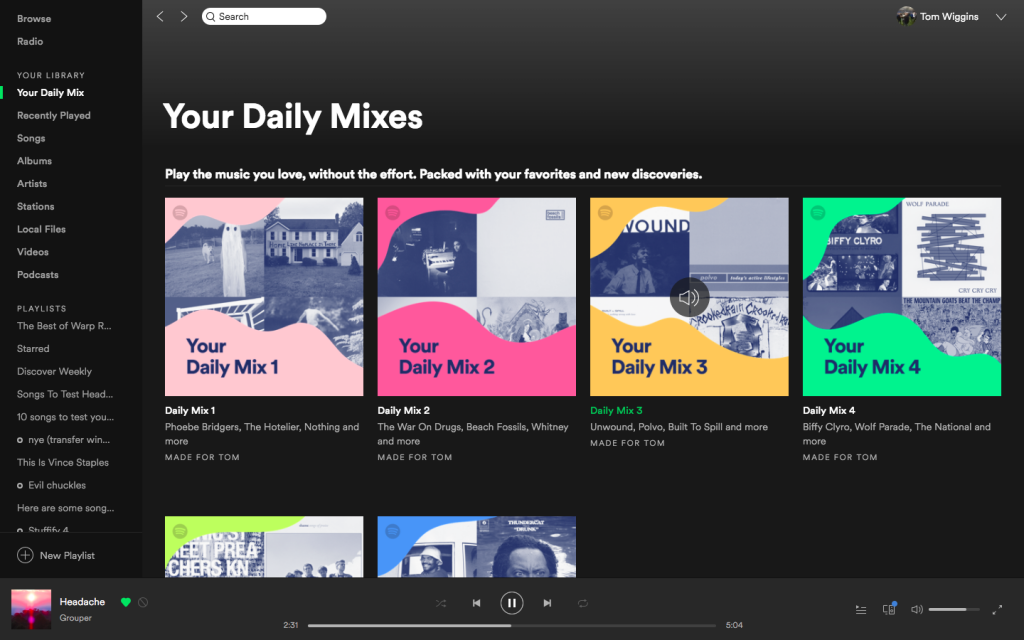

Spotify’s playlists aren’t personally curated, but the site’s algorithms create sequences as personal as even the best mixtapes. The genre and mood-specific playlists are just the beginning. In 2016 the website introduced “Daily Mixes,” playlists that reflect the different facets of each user’s musical tastes. As one streams more diverse music, Spotify creates more Daily Mixes, and they change styles with the user.

The “Discover Weekly” playlist was introduced the year before and has since become one of Spotify’s most successful features. The playlist refreshes itself every Monday with 30 recommended songs for every user,. The playlist is meant to introduce users to new music, or “songs we think you’ll love,” according to Spotify’s website.

“Based on what you and those with similar music tastes listen to, it gets even better the more you use Spotify,” the site’s support page explains.

Sophia Ciocca, a software engineer at The New York Times, explained the science behind the Discover Weekly in a Medium article last year. Acknowledging past streaming sites that paved the way for Spotify’s success, Ciocca said the site’s developers mixed the models of yesteryear when creating the algorithm.

The first model, ‘collaborative filtering,’ has notably been used by streaming sites Last.fm and Netflix. Spotify tracks ‘implicit data’ like stream counts, if the user saved a specific song, and if the user visited a specific artist’s page to determine if the user liked a particular song. After comparing the preferences of different users, the site can establish similar listeners and then recommend songs the other enjoyed.

Photo courtesy of Trusted Reviews

The ‘natural language processing’ model examines words instead of user history. The system scans the Internet for blog posts and articles that mention specific songs and artists, creating a composite of the words used to describe the music. These adjectives, as well as the names of artists commonly mentioned alongside each other, are part of the knowledge that informs Spotify’s recommendations.

While these models examine in some capacity the user response to music, the third, ‘raw audio,’ examines the music itself. “Convolutional neural networks” spit out data regarding a song’s time signature, key, tempo and loudness; Spotify then looks for songs with similar characteristics to be lumped together for potential recommendations.

By studying the fundamental characteristics of a song, the raw audio model allows lesser known artists the chance to be placed in a Discover Weekly playlist. This third model, then, serves as a catch-all for independent artists fewer people may be listening to and discussing online.

Spotify’s playlists recently gained another method of diversification. This October, the site allowed artists to submit unreleased music to its editorial team as a request for playlist placement, Rolling Stone reports. The artists’ frequently asked questions page assures the curious that submitting a song doesn’t guarantee a slot on the editorial playlist, nor can an artist pay to increase their chances. With the popularity of Spotify’s playlists, artist submission is a win for both artists seeking exposure and listeners seeking new music.

Playlists, even if created by users themselves rather than Spotify’s sciences, remain a hallmark of the streaming age. The concept of compiling individual songs rather than sticking to packaged albums has been bolstered by the accessibility of the Internet; Spotify boasts over 40 million songs.

“I make moods,” freshman rhetoric and writing major Rose Torres said of her playlists. “I have moods for , rainy days and And then I have one [for] ‘I’m so sad’ days, and I have one like ‘Songs to Sing in the Shower.”

For every argument that the Internet is impersonal, there’s a playlist for the most specific human emotions. Who’d have thought a machine could understand you so well?