With the advent of social media comes the immense pressure for people to present idealized versions of themselves. Luckily, “finstas,” private Twitter and Instagram posts meant for close friends only, allow people to reveal less polished versions of their lives, toeing the line between social network and diary. But how do you decide who to let in? And better yet, when does it begin to feel exploitative?

Story by Meghan Nguyen

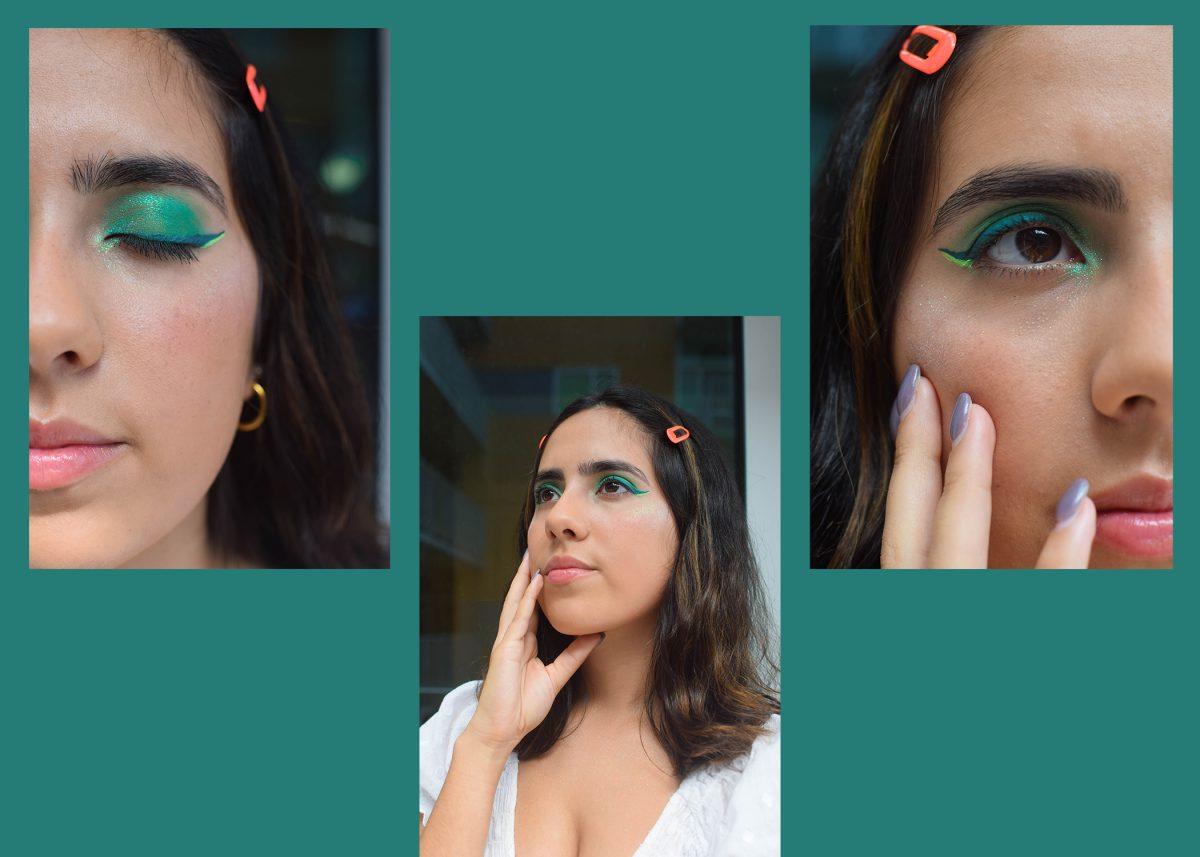

Photo courtesy of Daniel Hou, @daniel4hole

For millennials and Gen Z-ers, Instagram and Twitter function as the epitome of online self-presentation. Users under 35 make up more than 70 percent of Instagram’s more than 800 million active accounts worldwide, and 40 percent of U.S. adults who use Twitter are aged between 18 and 29 years. On those apps, you’ll find selfies, food pictures, and snapshots and tweets of candid moments, all captured in perfect light and enhanced with filters and editing tools, which serve to present an idealized image and to build a personal brand. Your Instagram and Twitter feed are supposed to scream, “This is the person I am; this is my life. Are you jealous yet?”

In reality, life is often emotionally turbulent, messy and wild, and more young adults are starting to turn to “finstas” and private Twitter accounts to capture these unfiltered moments. Finstas and private Twitters can house a broad spectrum of content, from shitposts to ugly selfies to long, depressive monologues that only a select following will be able to see. In fact, the hallmark for insta and private Twitter accounts is their highly curated followings— it’s not uncommon for these accounts to have followers purposely kept in the low double digits. This is so that users can feel free to be as honest, as depressed, and as indulgent as they want without judgement.

While young people of every generation have struggled with how to express and project their identities, young internet users of today arguably have it worse. Given the pervasiveness of social media and the pressure to present oneself as “always employable,” millennials and Gen-Zers can expect their online personas be surveilled and monitored 24/7. The feedback mechanism never shuts down. So at a time of life that is crucial to their identity formation, young Internet users of today are coping by creating their own intimate online spaces, on their own terms.

Diana Hinojosa, a marine biology sophomore, said her finsta and private Twitter gave her an online platform for sharing her thoughts with a small group of close friends. “I use my private Twitter and finsta to vent and blow off steam when I’m going through an emotional event or when I just want to shitpost to a select few of friends rather than my whole following,” Hinojosa said. “I tend to post a few times a week on my finsta… I post on my private Twitter every day though, since I find it easier to just compose my thoughts into a thread rather than an Insta post.”

Principles that guide Instagram and Twitter are gleefully thrown out the window when it comes to private accounts. While posting more than once or twice a day to a main account is considered borderline tactless, it’s perfectly acceptable on a finsta or private twitter to unleash a stream of ugly selfies, memes and minute details about an awkward personal encounter.

But how do you decide who deserves to see your private content? Are finstas/private twitters limited to close friends only, or just people you generally trust? Deciding who makes the cut isn’t always obvious, because inner circles can be fluid. In addition to that, users have to be careful about backstabbers, or people who could take screenshots of revealing posts and use them for leverage.

“Usually if someone else has a finsta that I follow, or if they’re a close friend that I trust, I let them follow my finsta,” journalism junior Shelby Woods said. “I’m super careful about who I let follow my finsta, even though I don’t feel like I post anything super bad or private. It’s an outlet for me, and since I only let close friends follow it, I feel like they (should) already know me pretty well anyway.”

Finstas and private Twitter accounts can be therapeutic, serving as a public diary and outlet for users who want to challenge the performativity of social media. However, it’s important to note that over-reliance on these intimate online spaces can quickly go south– users can find themselves commodifying their emotions and feelings and performing for an audience rather than using their finstas/private Twitters as an authentic outlet.

“When I was at a dark point in my life, I depended on posting every emotion I felt and dealt with on my private accounts,” Hinojosa said. “Sometimes I felt as if I would exaggerate how I felt for sympathy or to gain attention as a plea for help. I had to step back and realize it wasn’t healthy to depend on a private account to unload my baggage. It helps to let off occasional steam but I had to resist venting about anything an everything and instead keep a journal for myself rather than broadcasting my every thought to 40 people.”

Instead of responding to this epidemic of finstas and private twitters with moral panic, we need to recognize that they were created to circumvent a culture of constant monitoring and surveillance. We should also question the implications of an economic environment where young people are expected to be always presentable, employable and mild-mannered. Private online accounts seem to be a distinct cultural product of people belonging to a generation raised using social media and smartphones. Ultimately, we need to be aware of how these accounts are serving us and build more agency around how we interact with them.