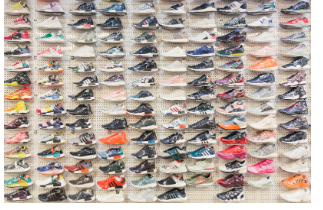

In November 2017, Nike released its Air Force 1 sneaker collaboration with luxury brand Off-White for a retail price of $150. By July 2018, the shoe was valued for over $2,000 on StockX, an online marketplace for limited edition sneakers. How did a white sneaker become such a valuable commodity?

By Bailey Cho // @baileyhcho

While the flip practice has been active for decades, the sneaker resell business truly emerged in the late ‘90s in metropolitan cities like New York. Mom and pop shops began selling exclusive sneakers under the table to locals, usually before official release dates. This shady advantage allowed small family-owned businesses to remain competitive with large scale retailers, but brands like Nike quickly caught on and cut ties with shops that participated in such practices. During this period, big brands began to realize the high demand for unique, limited edition sneakers, and this would increase the exclusive nature of the sneaker game. Brands began producing far less supply than demand and the Internet transformed the relationship with consumers at the turn of the century.

Photo courtesy of GQ Magazine

Sneakerheads began waiting in endless lines after release dates were announced for new products and those who waited would stock up. If you camped out overnight, it only made sense to buy a pair for yourself, your collection and for your friend who couldn’t make it. Initially, this commitment came from a personal need to cop the dream sneaker, but the continuation of limited supply and the accessibility of the Internet introduced a more capitalist approach. eBay and Craigslist became the primary markets to sell sneakers online, but questions of authenticity and safety arose accordingly. This allowed consignment stores including Flight Club and Stadium Goods, as well as websites like StockX and GOAT, to assist in more secure transactions. Thus, many retailers moved away from in-store releases due to potentially dangerous conditions. Today, Nike’s SNKRS app provides all the information regarding sneaker releases, including a randomized raffle process to increase “fairness” among consumers. These digital platforms have proved their longevity in the marketplace as well.

Photo courtesy of Racked

From the perspective of a reseller, the heightened price tag of sneakers represent the price of labor – camping overnight, bribing employees and security guards and purchasing bots to automatically add multiple pairs into carts right after online releases. However, there is definitely ambiguity regarding the ethics of the profit margin. Even though brands release a limited number of sneakers, resellers are able to profit three times more than people who work months on a sneaker project. Who is the villain in the resell business? Is it resellers, brands or consumers who constantly add hype to material items?

Photo courtesy of GQ Magazine

Overall, sneakers have always represented the most democratized form of footwear. Regardless of race or socioeconomic status, sneakers express where you come from, who you admire and what you are interested in. Many people claim the resell business ruined the sneaker game, but reselling has always been part of the culture – reselling without the love, knowledge and respect of sneakers has done the damage.