By Sam Limerick

Dozens of people stand scattered across the lawn at Eden House Co-op on the night of Friday, Aug. 29, enjoying one last hurrah at the start of a new school year. Some chat with friends or kick back on a pair of couches facing the road. Others filter into the packed house, where bands play to a jovial crowd. Suddenly, police cars wash the house and all of its guests in hues of blue and red. Plastic cups drop to the ground in a resounding clamor. The party is over.

Eden House Co-op is a hotspot for parties, concerts and other events. The co-op is located at 21st Street and Rio Grande Street on a stretch of West Campus that some call “Co-op Row.” Police cited William Salazar, the house resident responsible for planning and organizing its events, in the aftermath of the bust for “not having a permit for an assembly of more than 49 people.” This charge is part of the City of Austin’s new push to enforce party and sound restrictions in university neighborhoods, potentially putting the future of West Campus events in jeopardy.

As it turns out, the bust at Eden House was not prompted by any noise complaint. The police and fire marshal simply used the gathering of people on the lawn as grounds for shutting down the party, Salazar says. Authorities can use suspected fire code violations, which occur as a result of these large “public assemblies,” as cause to quickly shut down events.

On Sept. 3, officials from the Austin Fire Marshal’s office, the Austin Police Department and Code Enforcement called a meeting with representatives from the Greek and Co-op communities to announce a step up in the enforcement of sound ordinances. This includes crackdowns on illegal live music, as well as greater stringency in granting event permits, The Odyssey reported. At the meeting, Lt. Brad Price of the Austin Fire Department said that the crackdown was demanded by older West Campus residents, who claimed the city wasn’t doing its job in enforcing sound codes.

In response to such issues, the city has formed PACE, or the Public Assembly Code Enforcement. The task force is dedicated to preserving the quality of living for Austin residents, and addresses issues such as the safety of temporary structures, fire code hazards, enforcement of alcohol-related laws, noise ordinances, security and permitting for public assemblies.

PACE works closely with the fire and police departments to keep a more watchful eye on West Campus events. Billy Thogerson, general administrator of the Inter Cooperative Council, which manages many West Campus co-ops, addressed the issue in an email to all ICC members. “Instead of checking on only the frat parties five to six times per year, they plan on having inspectors in West Campus on the lookout for non-permitted public assemblies every weekend during the fall and spring,” the email says.

Technically, none of this should come as news to West Campus residents. These regulations have been in place for roughly 10 years but have been largely ignored by student residents until now. Having served as both a party hub and jumping-off point for a number of aspiring bands, West Campus is now at risk of losing the elements that have made it such a beloved staple of college living for many students.

English and women’s gender studies senior Sasha Henry lives at 21st Street Co-op, where concerts are held regularly, and encourages students to take a stand against these new ordinances. “News flash, West Campus is populated by young, loud people,” Henry says. “We’ve got to fight for our right to party!”

And fight they have. Students gathered in front of the UT Tower on Sept. 25 for a “West Campus March” to make their voices heard. Meanwhile, an online petition to “Keep Live Music In West Campus” has nearly 3,000 signatures.

The root of the complaints lies in the zoning of West Campus, which is classified as a residential neighborhood. This makes the predominantly student-occupied area (though it does house some UT faculty and staff, as well as retirees) subject to the same restrictions as Hyde Park or any other residentially zoned area in Austin. Given the unique environment that encompasses co-ops, fraternities and a large percentage of the general student body, there is some discrepancy in the way students and the city classify West Campus.

“While I agree that there should be a noise ordinance for residential areas, at the end of the day, this is West Campus,” says Taylor Ellis, vice president of communication for the Interfraternity Council and an active member of Sigma Alpha Mu. “The majority of people who live there are college students, and the ordinance seems more geared toward suburbs and residential areas further away from campus.”

Ellis says the council has been talking with city officials since the September 3 meeting to obtain exemption from the ordinance. “We are confident that we will be able to find a resolution to this issue in the coming months,” he says. “I think there are so many different options for how we could come to a compromise. It’s just a matter of keeping an open dialogue going and continuing to serve our fraternities.”

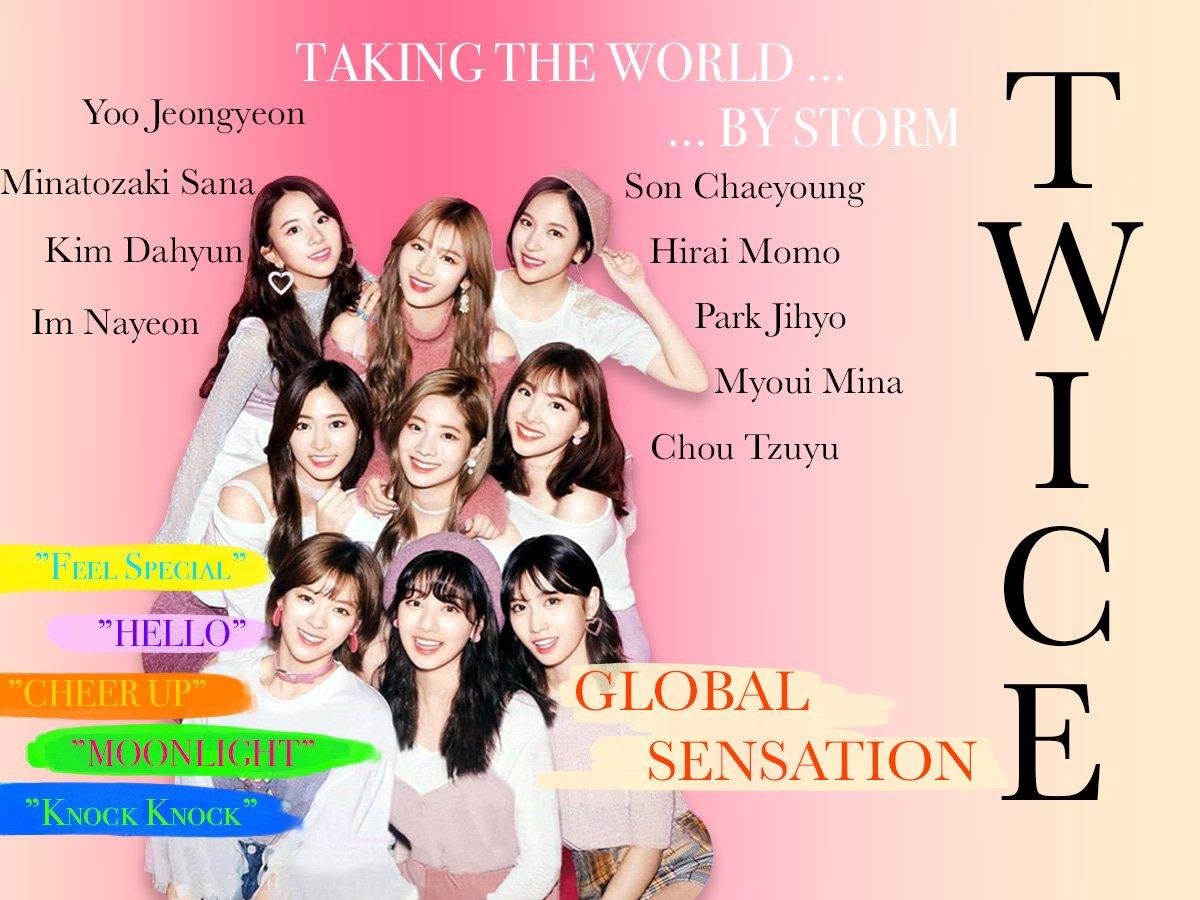

One of the IFC’s biggest concerns is Roundup — an annual, weekend-long event where many of the council’s fraternities throw parties and host performances from high-profile artists, like A$AP Ferg and Waka Flocka Flame. PACE’s amped-up enforcement will put an end to these concerts, which some members of the Greek community think will make the longstanding tradition more dangerous than in years past.

Ellis predicts that the removal of concerts will force fraternities to throw more parties at once, leading to overcrowding in parts of West Campus. “It is better, in my opinion, to allow fraternities who are raising money for good causes to be allowed to hold these events at night to spread out the times throughout the day,” he says, referring to both day parties and nighttime musical performances. There is a general consensus among most of the West Campus community that a more nuanced dialogue between city and student body is necessary to preserve the traditions and culture of the neighborhood.

“Students use these areas as a venue to express themselves and to rejoice in the newly discovered freedoms that are accompanied with student life,” Salazar says. “I hope that there will be some sort of ease of enforcement of these rules, or what I would prefer is a complete scrap of the PACE system for another set of rules that involves fraternities, sororities, cooperatives, student government and the city in complete dialogue.”

Perhaps this sort of compromise can be reached next month, when Austin sees its first city council election. Spots on the council are not decided by citywide votes. Instead, Austin will be split into 10 geographic districts, with one representative elected from each. The University, West Campus and North Campus areas are all included in District 9.

Salazar encourages all students who are concerned with these policies, whether they attend events, play in a band or plan parties, to get involved and vote. He insists that their voices are loud enough to effect change. “Students make up 25 percent of the voting population in District 9. We are a sizable enough community that we could change the course of these policies,” Salazar says.