This summer, I had the opportunity to spend the entirety of June and July studying abroad in Sydney. I was terrified; I had barely been out of the country, let alone on the other side of the world in a city where I didn’t know anyone. Luckily, it soon turned into one of the best experiences of my life. I made friends, discovered new cultures and did things I never thought I would do, such as surfing and trying a horrible vegetable spread called “Vegemite”. One thing that I was not expecting was actually learning something. I know, supposedly that’s the “whole point” of studying abroad. However, my lessons were not learned in the classroom but from observing the society of Australia.

Australia is like America in a lot of ways. We speak the same language, teens sneak into clubs, there is a McDonald’s on every corner (although it’s charmingly called “Macca’s” over there). But Australia is ahead of us in several ways. Here are some things that I think our citizens and government should take note of:

Some Long Overdue Respect

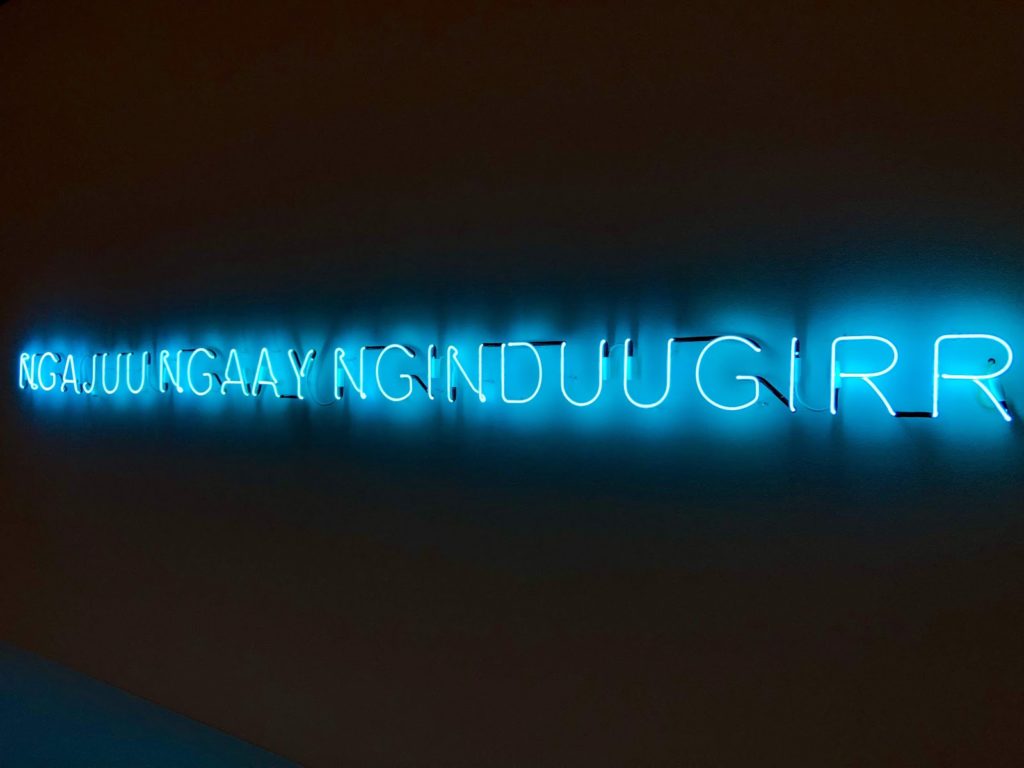

Saying “I’m sorry” is a common courtesy; this is common knowledge. You would think that a whole institution could, at the very least, apologize for causing a genocide of an entire nation’s indigenous peoples. The United States has yet to have that epiphany. Australia is slowly getting there.

“National Sorry Day”, also called “National Day of Healing”, is a nation-wide Australian holiday that is celebrated every year on May 26th. It was established in 1998 under the rule of conservative Prime Minister, John Howard. Although the administration enacted the holiday, an actual apology was not given to indigenous peoples until a full decade later when Kevin Rudd took over as Prime Minister in 2008. The holiday is meant to pay homage and respect to the past treatment of the Aboriginal community, especially the Stolen Generations.

The Stolen Generations were children that were forcibly removed from their families between 1910-1970 throughout Australia. This was done under the policy of “assimilation”, in which white government officials separated Aboriginal children from their families and forced them to reject their heritage and adapt to “white culture.” Many of the children that were displaced were subjected to unimaginable trauma, including but not limited to sexual abuse, lies about their parents being dead and physical beatings.

In addition to the national holiday, all of my classes at the University of Sydney started with a statement called an “acknowledgment of country.” It goes something like this: “I acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land on which I work and live, and recognize their continuing connection to land, water, and community. I pay respect to Elders past, present and emerging.” It’s the least someone can do when teaching or living on stolen land and yet we lack something similar in our own classrooms.

This is not at all to say that Australia’s progress makes up for the horrid treatment that the Aboriginal community has and continues to endure. But it’s a start. A better start than we’ve ever had.

The Stolen Generations is reminiscent of the cultural assimilation that Native Americans were subjected to in the States for over 100 years. From 1790-1920, Native Americans were forced from their homes and onto poorly managed reservations, their children were required to go to “boarding schools” that stripped them of their culture and many of their tribal traditions were outlawed. The few things listed are only a taste of the atrocities that were inflicted.

Some may argue that we have made restorations, we have said sorry. On the contrary, my friends: the largest “apology” that has been offered was the Native American Apology Resolution that was signed on December 19, 2009, by former President Barack Obama. It sounds great but the exact words are that the president “apologizes on behalf of the people of the United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States.” As the Indian Law Resource Center points out, there is no formal apology made by the government itself and it does nothing to support any legal claims by indigenous tribes against the States. In addition to the lack of care or coverage of that historic apology, there is no acknowledgment in any form, not in schools or in public parks or anywhere, of the ancestors that came before us on this land. No one acknowledges the bloodstains that still blemish the earth.

So why don’t we have a national day of remembrance for our own stolen generations? Why do we celebrate “Columbus Day” instead of Indigenous Peoples’ Day? Why don’t tribal leaders have more say in federal and state legislation? Why is it so hard to say sorry?

Oh Yeah, That’s Not a Thing Here

Not only did my temporary college look like something out of a J.K. Rowling novel but it was also…safer. I hadn’t thought much about it until something happened one day in class that slapped me harder than any epiphany I’ve ever had.

We were in our discussion section, talking about the reading we were assigned the night before. It was early in the morning and I hadn’t had my coffee so my eyelids were more than a little heavy. Suddenly, rushed footsteps came barrelling down the stairs outside of our lecture hall. My eyes burst open. My heart started pounding. It’s a shooter, I thought.

But then the feet kept running down the steps as a student rushed his way to class. I relaxed. I remembered. Oh yeah, that’s not a thing here. They have effective legislation.

Australia hasn’t always had strict gun laws. A few decades ago, their gun laws were similar to our own. But on April 28, 1996, a 28-year-old gunman went on a killing spree in the popular tourist area of Port Arthur in Tasmania, killing 35 people and injuring another 18. Within weeks of the horrific tragedy, on May 10, lawmakers in Australia worked together to quickly pass the 1996 National Firearms Agreement. This policy banned semi-automatic guns and other military-grade weapons, as well as the government buying back thousands of these guns from their owners.

Studies have shown that the ban on rapid-fire weapons has resulted in a decrease in homicides, suicides and mass shootings in Australia. This is not because of “thoughts” and “prayers” and blaming video games. This is because of quick and smart legislative action.

Mass shootings have been all too common in our country. As of September 9, 2019, we have had to suffer through 289 mass shootings this year alone. If I had heard those frantic footsteps down the steps of a UT building, I would’ve ducked under my desk or fled for the nearest exit. Our lawmakers have yet to do anything to change that. Perhaps they could take some tips from our eastern hemisphere friends.

It’s Not That Hard

Do you know what’s missing in this photo? Trash. There was never any garbage littering the shores of any beach I went to. Australians take great care of their island. Their country is about the size as our own, only lacking in about 2 million square kilometers.

Litter was very uncommon. Of course, it’s not unheard of, especially in the city. But Bondi was a far cry from Galveston and Coogee was a whole other world compared to South Padre Island. The only difference between there and here? The people actually care. They want to keep their home beautiful. It’s not that hard to try.

Keeping the beaches clean was not the only betterment that the Australian peoples did to help their environment. Almost every toilet, from the hotels to the gas stations, was water-conserving. There were two buttons on the top, one for liquid only and the other for…more mass. It surprised me that they were everywhere but it also brought me joy. Flushing a toilet is not something you think of as being detrimental but conserving water has many benefits, including reducing water pollution, fewer chances of damaging water quality and improving water management. Most bathrooms also featured Dyson hand dryers, the ones that quickly dry your hands in a little tunnel and reduce paper towel waste.

In addition to the toilets and cleanliness, Sydney was much more open about their recycling policies. They encouraged people to do it wherever they went and stores offered recyclable plastic bags for a small fee. It was small things like this that I hardly thought about before going to Australia. Now they’re all I can think about when I see people being lazy or wasteful about our environment.

There was a woman in an Uber I was with one night who had been born and raised in Sydney. Her son had just graduated from the University of Sydney and we were discussing how I was enjoying my time abroad. I told her that everything was cleaner there and I loved it. She made a face. “What?” she asked. “Everything’s dirtier here in the city.” Girl, you have no idea how good you have it.

G’Day? Crikey? Excuse me?

Every time I told someone that I was going to Australia, they told me that I was going to killed by some form of a poisonous animal. I knew it was unlikely but I listened to every joke because everyone thought they were being original. But there was a part of me that thought there was some truth to these ominous predictions.

Contrary to the warning pictured above that was on a beach in Cairns, Queensland, the only dangerous animals that I encountered were in a zoo. I never even saw so much as a spider during my time there. I was kind of disappointed in my lack of endangerment but it made me think about the stereotypes I held about the country I was visiting.

I feel like people tend to think that everyone down under walks around in Crocodile Dundee hats, calling each other “mate” and saying “crikey” and “g’day” every chance they get. Although they do say “mate” a lot, I only heard “g’day” used twice and I never once heard someone use “crikey.”

No, these stereotypes are not necessarily harmful. However, it made me consider the other stereotypes we all hold deep in our minds. They may not seem harmful but they’re still misconceptions held about an entire group of people. It’s a dangerous thought process that we’re all guilty of. So even though you may be “just teasing” someone, don’t make it a habit to hold onto stereotypes.

Living in Australia taught me many things. Smoking was very prominent in Sydney and reminded me of how much I hate it. Trains are, in my experience, a much more reliable form of transportation over Cap Metro. I learned to be more comfortable with a certain word starting with the letter “c” and to even feel flattered when Australians use it as a compliment. All in all, Australia opened my eyes in many ways. I hope, someday soon, we can all take a look at the world around us and learn lessons to better ourselves.