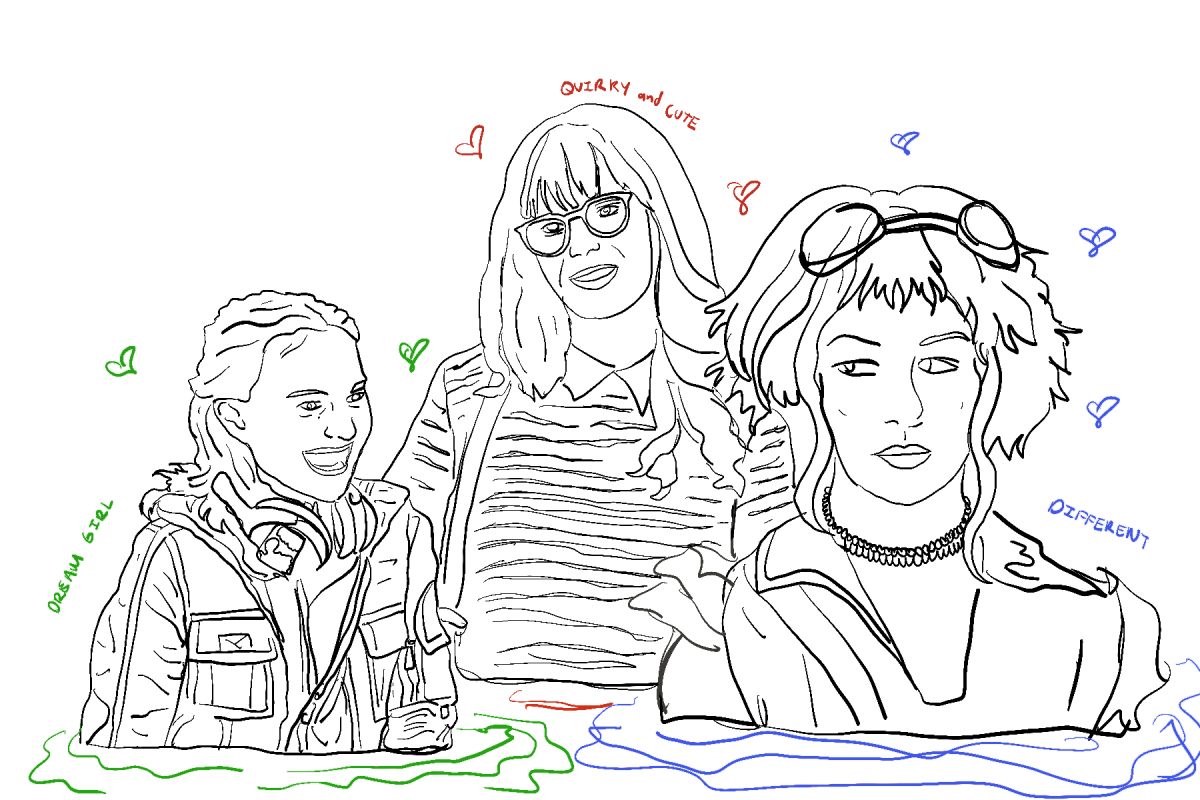

So, you have dyed hair, a mysterious past, and a bubbly personality. You also love your flawed yet lovable protagonist. So, congratulations! You might be a Manic Pixie Dream Girl!

We’ve all seen the movies and heard the stories: the bubbly, kind female love interest falls for the dark, brooding male protagonist. His life magically changes overnight when the quirky female love interest walks into his life, forever changing his edgy ways, and they live happily-ever-after, “The End”. But what exactly is the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope? Where did it come from, and who, if anyone, is the first MPDG?

The History

The term Manic Pixie Dream Girl was first used to describe Kirsten Dunst’s character in the film Elizabethtown. Her character, Claire Colburn, is the romantic lead opposite of Orlando Bloom’s character Drew Baylor. Drew slowly realizes that he is in love with Claire as he wades through his own issues of doubt and self-pity. A fairly standard MPDG plot, Claire gives her all emotionally and physically as the pair meets in rather unlikely circumstances. Claire seems to care so deeply about Drew upon their first meeting, despite knowing little to nothing about him.

Film critic Nathan Robin used the term as he described her character, along with other MPDGs, to “exist solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” This description fits perfectly for the male protagonists who are often paired with MPDGs such as Drew Baylor from Elizabethtown, Scott Pilgrim from Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and Andrew Largeman in Garden State, all of whom are brooding, edgy, down-on-their-luck male protagonists whose lives change upon meeting their perfect, effortlessly cool MPDG.

However, the history of MPDGs can be traced back much farther in film history. A “historical” example of the MPDG is Susan Vance’s character from the 1938 film Bringing Up Baby. Played by Katherine Hepburn, Susan is a free-spirited, scatter-brained ball of chaos. In the film, her erratic nature gets her caught in all sorts of zany problems with the mild-mannered protagonist David Huxley. However, throughout the film, David grows to love the state of confusion and chaos he finds himself in when with Susan. Susan, like Claire, is unsuspectingly brought into the life of our dull male protagonist, whose life is lit with joy as he meets his magical ray of sunshine, who loves and adores him.

MPDGs exist in film and other forms of media: literature, anime, and all other places where brooding writers are creating two-dimensional women. One such example, found in a rather unlikely place, is Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451. Yes, that is Fahrenheit 451. With the books and the fire that you read for high school Lit. Not exactly the romantic comedy akin to the films previously mentioned. The character Clarisse McClellan is often attributed to being one of the first MPDGs, with Ray Bradbury accidentally creating the trope. This has even gone as far as literary critic Jimmy Mahar going to say “Bradbury has been credited, with some truth, with foreshadowing… I’ve never, however, seen him properly credited for his most insidious creation: the Manic Pixie Dream Girl”.

The Critiques

Since the terms’ inception in 2005, the MPDG trope has been largely criticized (and rightfully so) for its diminutive use of women as plot devices and stock characters.

The main critique of the trope states that the MPDG reduces women who are inherently girly into nothing more than lifeless shells: useless unless involved with a man. The trope also lumps all female characters who have stereotypically MPDG-esque interests into one characterization, even when their lives and personalities are far greater than a one-dimensional trope. Again, this diminishes their lives, interests, and personalities as a whole into nothing more than feminine shells.

Meanwhile, this can’t be farther from the truth. Feminine characters are more than just their bubbly demeanor and potential to make good love interests. They are flawed, which supports a major critique of the MPDG trope. MPDGs are written as beautiful, perfect angels sent from heaven to save their male protagonist from a life of solitude. Any “flaw” is merely a perfectly planned quirk that the male protagonist finds adorably unique to his new love, leaving no room for imperfection. But real women are flawed and imperfect. We get angry; we have interests other than writing poetry in the moonlight and being devoted to our partner. We are whole, amazing people with personalities and lives of our own. Something that the MPDG trope doesn’t capture.

The Future

With the history of the MPDGs, to its origins in Kirsten Dunst, and a banned book about banning books, where does that leave the future for the MPDG? Well, no one really knows!

Rabin himself wishes he never used the term in the first place, claiming that the MPDG has since been used for sexist interpretations of female characters, reducing fully-fledged female characters into empty shells for male protagonists. Rabin believes that the term should be retired, and an end should be put to the cliche.

Meanwhile, some people have taken a new spin on the MPDG, subverting the trope to make girly, quirky characters who don’t care for the male protagonist. One example is Zoey Deschanel’s character Summer from 500 Days of Summer. The male protagonist Tom Hansen holds an idealized version of his ex-girlfriend Summer, showing the dangers of holding unrealized and incorrect views of real, living people. Meanwhile, the audience learns that Summer isn’t the perfect, angelic person Tom has in his head. Instead, Summer is a whole person, complete with a past and flaws that Tom chooses to remove from his perfect version of Summer. In this instance, we begin with a MPDG, beautiful, idealized, perfect. But, we leave the film with Summer. Complete, angry, imperfect.

It isn’t known what the true future of MPDG is. Some people hate the term. Some people relish it in, romanticizing their lives to their heart’s content (myself included). What matters is that women continue to be written as whole people, with histories, trauma, and personalities. They can love and hate and do everything in between. They can be their own protagonist.

Featured Image by Bettina Mateo