“Comma-la” or “Kuh-mala” never occurred to me. It’s just Kamala – neither syllable is enunciated more than the other. The name rolls off my Indian-American tongue naturally.

I wonder what the fuss around my name would be if I ran for office. The traditional way to say it is something like “Mun-dhi-ruh,” but as a child I couldn’t say my r’s and hated confrontation, so I’ve been “Man-dee-ruh” ever since.

“It’s easy. You say it just like it’s spelled,” I tell everyone who glances at me nervously before they attempt to say my name aloud.

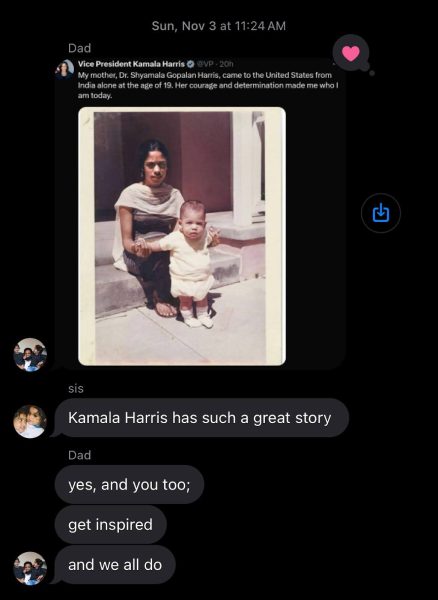

Seeing an Indian woman as the Democratic presidential nominee felt inconceivable — like the absurdity that Camus wrote about. I looked at her and I saw me. My parents looked at her parents and saw themselves.

It never occurred to me that Kamala Harris wouldn’t win the presidential election. Only half of her name was “exotic” and it didn’t have any secret Indian syllables that the English language doesn’t support.

To my surprise, existential philosophy is no match for America’s underlying misogyny and anti-immigrant sentiments.

Even my hometown of Redmond, Washington, which I regularly tout as a beautiful, progressive oasis to my Texan friends, is home to these same prejudices.

Washington State Sen. Manka Dhingra, is the first Sikh person (and Sikh woman) to be elected to a state legislature. She’s also my best friend Isha’s mom.

However, Dhingra has always been more than just “Isha’s mom” to me and my community. Prior to being elected to the senate in 2017, she served as a King County prosecutor for 20 years, creating policies and organizations to protect against gender-based violence and support mental health.

Dhingra’s first election came at a pivotal moment. After president-elect Donald Trump took office in 2016, Dhingra’s election was the first that would flip a seat in Washington’s state Senate. Her win would bring a Democratic majority to the Senate, House, and the Governorship, completing the “wall of blue” on the west coast.

“(Until) today, my race was the most expensive legislative race in the history of Washington,” Dhingra said. “There was a total of $10 million spent on both sides of this race, and $3 million was spent in attack ads against me.”

Winning elections as a South Asian woman is no easy feat. Anagha Kikkeri, the University of Texas’ first female South Asian student body president, said she had a campaign team of hundreds of her friends to secure her position for the 2020 to 2021 school year.

However, before college, holding a leadership position in the public sphere didn’t seem achievable to Kikkeri.

“I was always drawn to public service (and) public advocacy. I never contemplated doing anything else,” Kikkeri said. “I didn’t really understand, though, growing up, that I could work in this field. I never saw many women of color, let alone South Asian women doing it … it seemed like a very distant, far away dream.”

Kikkeri was born and raised in Texas to two South Indian immigrants from the state of Karnataka.

In August, just weeks after returning from a year-long Fulbright fellowship in India, Kikkeri joined Harris’ campaign.

Kikkeri worked as a late help specialist on the battleground team, recruiting and training full-time volunteers to support the campaign in battleground states.

“I think that (Harris) represents so much of the United States and the diversity that we hold — the multitudes that we hold,” Kikkeri said.

Harris, like Kikkeri and me, was born in the US to immigrants. Her mom immigrated from South India and her dad from Jamaica.

Growing up, I held on tightly to the little South Asian representation I had in the US. Whether it was Kelly from “The Office” or Ravi from “Jessie,” I felt like I only saw Indians fill one-dimensional, comedic roles. I rarely saw people like me in mainstream American culture and when I did, they were the brunt of a joke.

When people made fun of them, it felt like they were making fun of me. Watching the rhetoric circulating online and in the media about Harris disturbed me, both as a woman and an Indian woman. Purposeful mispronunciations of her name and claims that she “slept her way to the top,” felt so insulting as I saw Harris as a part of me — a better version of me.

Dhingra shared that this kind of misogyny and racism aren’t new, especially in the political sphere she’s in.

“I was the first South Asian prosecutor in King County. I’ve been the only woman– the only woman of color in lots of rooms my entire life,” Dhingra said. “I’ve had racism (and sexism) in my face my entire life. But nothing compares to the level of sexism and racism you deal with in the political world. In my (attorney general) race, the misogyny and the racism, even within the Democratic party, were tremendous.”

Dhingra recently ran for attorney general in Washington. Winning this election would’ve made her the first immigrant attorney general for the state. Despite seven years of experience in the state legislature and decades as a public prosecutor, Dhingra was unable to secure statewide Democratic support in the primary.

“One of the reasons people think I lost the AG race was because no one knew what a ‘Manka Dhingra’ meant, but they knew what a ‘Nick Brown’ meant,” Dhingra said. “They don’t know what that person’s name means (or) where they come from, it seems like the ‘other’– not one of them.”

Despite losses like hers and Harris’, Dhingra said South Asian representation is not a losing game.

“Every time our names are on the ballot, every time people see signs for our names, it makes it more acceptable,” Dhingra said.

Not only does representation make the South Asian community feel more empowered, but it also makes us as a country stronger.

“I think we only get better when our leaders connect with us more,” Kikkeri said. “So I look forward to our government looking more like our population.”

Through the ups and downs of this past year, my mind always brought me back to the family dinner parties I grew up with. The smell of chapatis roasting directly on the fire, the murmur of a Bollywood movie playing in the background, my dad’s high-pitched laugh that only comes out when he’s telling stories in Telugu. In this memory, I’m at the dinner table, listening to the uncles and aunties pestering me about my grades, joking that they couldn’t be the first Indian president, but that my sister and I could.