By Maddy Hill

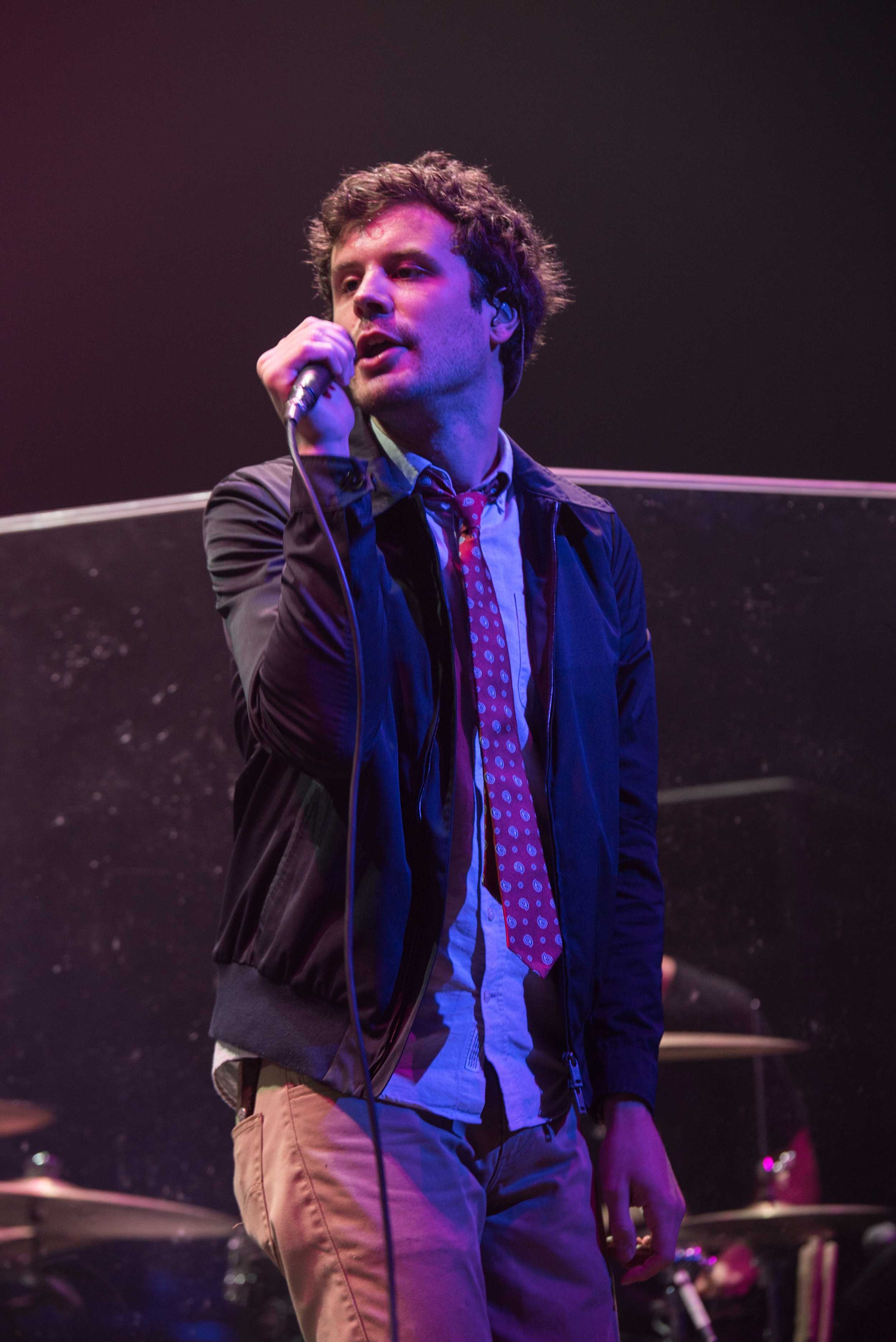

Sitting on the brown crushed velvet couch in the media room of ACL Live at Moody Theater, surrounded by copies of his latest album, Passion Pit lead singer Michael Angelakos looks relaxed. But under his calm demeanor is a man who’s experienced enormous adversity in recent years and come out on the other side.

Passion Pit released “Kindred,” their third full-length, in April and have since toured on their own and as a headliner for the Mercedes Benz Evolution Tour. Meanwhile, in the past few years, Angelakos has spoken more truthfully about his struggles with bipolar disorder, which caused him to cancel a string of shows in July 2012. Angelakos channeled these struggles into the band’s previous album, 2012’s “Gossamer.”

Angelakos sat down with ORANGE to shed some light on the music making process, the connection between the band’s three albums and how he copes when it all becomes too much to handle.

ORANGE: How do you think your music resonates with millennials specifically?

ANGELAKOS: When I was first writing the music, I was 19. I was really emotionally frustrated with everything happening in my life, and confused. Millennials are criticized a lot. The Internet has trapped a lot of emotions and made things both accessible, but more confining. I don’t know how to properly express it, but there’s just this caged, weird feeling I get that’s kind of involved with all the issues surrounding millennials. Technology has screwed up a lot of people. It’s a transitional period. I don’t know how technically [my music resonates with millennials], but I can feel that there’s probably some real connection.

O: How do you express yourself in spite of creative restrictions?

A: You have to just do it. It’s terrible to say it like that, but you have to pretend that all of these self-imposed restrictions are not real. You have to just go for it and attempt to be heard, because someone will hear you, and there is someone out there that will listen at some point. I do think that was a struggle that I can identify with. I understand.

O: Why is “Kindred” such an important album in your career?

A: I like that I set out to do something and actually accomplished it. I wanted to make a record that was the third installment in a trilogy-type thing. I wanted the sound to be very specific. I wanted to nail down what the Passion Pit song sounded like — all of these sonic characteristics I went through meticulously. I just wanted to actually make a good Passion Pit record, and I knew that wasn’t maybe going to be my best record. But in five, six years, people can look back and be like, “These three albums together make perfect sense.”

O: Which they do.

A: It’s a cohesive body of work. That’s what’s important to me, is how it’s going to work in five or 10 years. I didn’t really care if people were going to love it right off the bat. I wanted it to make a ton of sense in the future. I always was thinking in terms of in-the-moment, which is boring. I like thinking larger scale.

O: Speaking of in the moment: when you perform, you get very wrapped up and it’s emotional for people to watch you perform. How do you get to that place?

A: I have no idea. Ever since I started performing, which was when I was really young, I just go out and it’s a switch — I just flip it. You’re on stage and that’s it. I don’t really remember much from the stage and my performance. I don’t know what it is, but I can be in the worst mood and go onstage and that will still happen.

O: Is music therapeutic for you in that sense?

A: It’s a part of me. Therapy is something that is extrinsic. I just get to be this weird version of myself for a few moments, and that’s just relieving. It’s a drive, just like anything else. You have to eat, you have to sleep. I have to be crazy for a few moments.

O: When you first started making music to put on iTunes, did you consider what other people would want to listen to? Or was it always what you wanted it to be?

A: I started it to make my friends happy, and I wanted my friends to dance and enjoy it, so I was already thinking about other people’s opinions. That was a lot more comfortable. When I got much more into releasing records on a major label, for sure I started over thinking a little bit what people wanted. It’s never led to anything that anyone’s even liked, ironically [laughs]. You learn it’s about really dialing that in and figuring out how to filter those thoughts, because it’s natural for any medium, really.

O: Do you ever jam out to your own music?

A: Very, very rarely, but a song that we don’t perform live or something like that. I remember not so long ago, I just put on “On My Way” from “Gossamer.” I love that song. It’s one of my favorite songs I’ve ever written, actually. It’s really pretty and it’s really sad. I remember how I wrote it, too.

O: How did you write it?

A: Literally in the pitch black studio I had in Dumbo [neighborhood in Brooklyn] before I got a new one. I was drinking at the time — what is it, Four Loko? I was alone, just drinking this Four Loko, and it was so odd but I just kept going with it. I was like, “This is a terrible circumstance, but this is really pretty.” I kept going with it, and thankfully I recorded it because I don’t remember anything that happened after that. I just remember coming back to it the next day and thinking, “This is awesome! This is great!” I just can’t write like that ever again.

O: Is there a certain mindset you have to be in to create music?

A: As long as I’ve got my proper dose of caffeine and everything, I’m thinking about it. Every day. I wish I could be doing it all day, dedicating time to it. But I’ve gotta do other things that humans have to do.

O: What can you say to someone suffering from bipolar disorder, depression or anxiety and feels it is all-encompassing?

A: It feels as though there’s never anything anyone can say that’s going to make anything feel better. But the secret is that even though it’s painful and you don’t want anyone to tell you that it’s going to get better — because I know, I have been in situations recently where it’s just like, shut up, there’s nothing that’s going to make this feel better… If you can remember you’ve gotten better and find that in your brain and try to remember the feeling when you didn’t feel depressed anymore, you can start to chip away at depression.

Depression is not something that’s an exponential curve. You don’t just sift in and out. So people and artists — especially artists — don’t understand that you slowly chip away at a euthymic period, a period of feeling normal. It doesn’t just get better. It gets better in pieces… You have to keep thinking about the feeling of knowing you were fine. Allow people to tell you it’s going to be okay, even if you think and feel that it’s not.