Mental illness has always been a part of me. Maybe it was a rocky, and at times traumatic childhood, or maybe it’s the way I was born. But what if there’s something wrong with me? What if I need to change?

Almost every person struggling with mental health has asked themselves these questions at some point, including myself. This internal struggle remained constant for most of my life, but as I grew older, I realized that this was an illness and I needed to take care of it like I would any other with the right treatment.

There are a variety of treatments for this, medication being one, all of which come with a list of side effects and stigmas. Some of the more popular medications include Lexapro, Prozac and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs.

Around 60% of college students suffer from mental health challenges, with almost 40% taking medication for this in 2023. Several doctors believe that they are an effective treatment option, but alternatives like therapy should also be considered.

Since I was a kid, I knew I didn’t meet certain norms. While other kids worried about who was getting picked for dodgeball, I begged my teacher to let me sit in her classroom and finish my homework because of my debilitating social anxiety.

I’d always had anxious habits. One of the worst was calling my mom in the middle of the night at sleepovers to pick me up because I was too nervous to be away from home.

I knew this wasn’t normal, but it wasn’t until I had my first panic attack at my grandpa’s funeral that I realized I needed help.

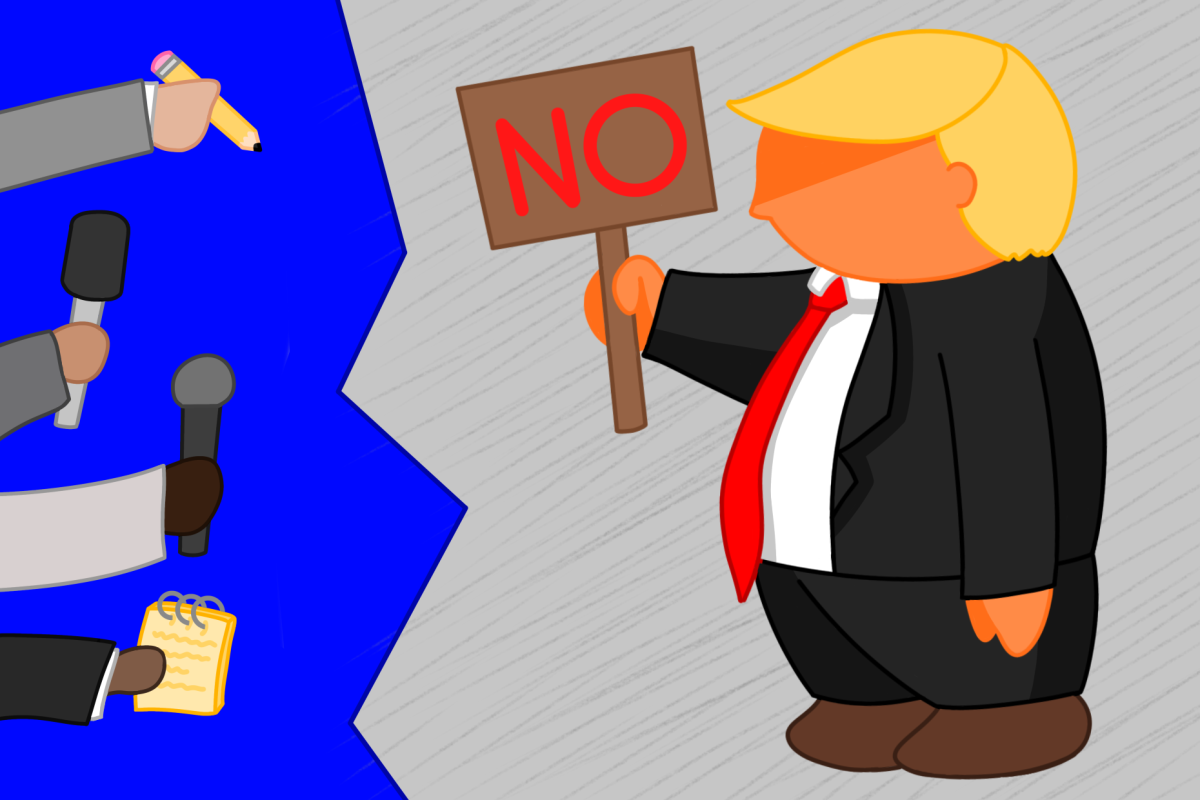

“My kid doesn’t need drugs. You’re perfectly normal,” is what my dad told me when I asked about seeking treatment for my obvious anxiety, which only seemed to be getting worse.

My self-doubt grew from there, and stemmed from growing up in a small, conservative East Texas town, with a family whose values aligned with that culture.

This challenge is something Melissa Eshelman, senior director and chief of psychiatry at CMHC, has seen many students struggle with and warned of the implications.

“Some families have negative perceptions of mental health, its symptoms and its treatments,” Eshelman said. “This cultural stigma can make it challenging for students to seek help, especially if they have heard negative comments from family members about mental health treatment or medication.”

My dad calling me “normal” when I knew I was anything but caused me to reevaluate who I was. By implying that people who take medication aren’t “normal,” he was furthering the embarrassment and shame I felt from needing it.

“I often hear the idea that seeking treatment or taking medication is a sign of weakness,” Eshelman said. “That couldn’t be further from the truth. Mental health issues are medical conditions that need treatment, just like conditions like diabetes.”

On the night my mom dropped me off at college, she was making the four-hour journey back to my hometown when I got up from my bed in Duren residence hall, tears streaming down my face, and went to the bathroom to call and beg her to take me home, like I’d done at all those sleepovers as a kid.

“I think we should consider taking you to therapy and trying a small dose of medication for your anxiety,” my mom said.

It wasn’t until last year that I was diagnosed with anxiety and prescribed Lexapro. I was humiliated. I had fallen victim to the stigma surrounding these medications my entire life, and now was being told that I needed one of them. Even worse, this “illness” that had been part of me was going to be stripped away and replaced by some medication?

I was worried I would lose the parts of myself that made me, me.

After taking the medication, however, I noticed almost immediately the improvement in my day-to-day life, especially when it came to my anger– the part of anxiety I had struggled with the most. According to a statistic from Crown Counseling, so do more than 40% of people suffering from anxiety.

After taking Lexapro for a few months, I noticed a significant difference in not only my mood, but my actions. I was much more calm and less reactive in volatile situations, which has improved my ability to complete normal, college-related tasks.

Not all mental health issues require medication, but if symptoms persist, worsen, or become severe—ongoing sleep disturbances, significant weight changes, suicidal thoughts, or inability to participate in daily life—then seeking professional help is crucial, Eshelman said.

Analee Tinajero, a theatre and dance sophomore, didn’t experience any major negative side-effects from medication, but she had questions before taking it, all of which were rooted in negative comments she’d heard.

“One thing I heard a lot of people say, and personally felt before starting Prozac, was fear. Who am I without my mental illness? Who am I without my anxiety?” Tinajero said.

Eshelman discredited this theory and shared that medication is prescribed to help people, not hurt them.

“One major misconception is that medication will change a person’s personality,” Eshelman said. “That’s not true. These medications are meant to relieve symptoms like fatigue, diminished appetite, or hopelessness, allowing a person’s true personality to shine through.”

Tinajero said she felt a sense of embarrassment regarding her condition and the treatment her provider prescribed.

“Whenever I started taking it, I didn’t tell anyone other than my best friend,” Tinajero said. “I (didn’t) want people to hear (I was) on antidepressants and be like, ‘Oh, she’s had a hard life. She’s messed up.’”

“Dismissive language”—calling someone “crazy,” “drugged up” or insinuating that there’s something wrong with them because of their illness—is something Eshelman said “contributes to stigma and makes it harder for people to seek help.”

“The thing that a lot of people ask me is if I feel like I’m on drugs all the time, or, ‘Do you feel all drugged up?’ No, not really,” Tinajero said. “I just take a small pill at the beginning of my day and feel more confident to talk to people because I have really bad social anxiety.”

After taking Prozac for a few months, Tinajero said the pros of taking medication greatly outweigh the cons.

“Ever since starting (Prozac), it’s so easy to talk to people,” she said. “It makes me sad how scared I was when it’s really not as huge of a deal as it seems.”

While this stigma around mental health and treatment is widespread, it’s not as bad as it once was, Eshelman said. She credits this partially to the rise of social media and growing conversation regarding mental health, which Eshelman said has encouraged “more willingness to seek treatment and interest in treatment options.”

However, the historical stigmatization of mental health disorders can prevent or delay people from seeking help. Some of the concerns stem from the real side effects of medication. One of the most rare and fear-inducing for people under 24 is suicide.

The FDA has issued “black box” warnings about a potential increase in suicidal thoughts when starting antidepressants, but findings have been inconclusive at best.

Some data suggests that they directly contribute to lower suicide rates, but other studies said that “children and adolescents taking antidepressants were almost twice as likely to have suicidal thoughts or to attempt suicide, compared to patients taking a sugar pill.”

For some people, though, medication simply doesn’t work, said Christopher Beevers, a professor of psychology at UT who specializes in the treatment, risk and maintenance of depression. Through his research, he’s found that it’s hard to predict who will and won’t benefit.

He recommends that people consult with their doctor throughout the entirety of their mental health journey, as it’s important to not become reliant on medications, even though he said the risk for that is low.

“I don’t think there’s a strong risk for physiological dependence, but there is some risk, which I think is partly why people often take these medications for quite some time, even beyond the depressive episode,” Beevers said.

Some are hesitant to stop taking the medication, fearing they’ll become depressed again, even if they experience side effects, Beevers said. He recommends only taking medication for certain depressive periods, and considering other treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, for long-term assistance.

“There’s pretty good evidence that (CBT) is about as effective as medication and may be more effective for preventing relapse,” Beevers said. “With CBT, the lessons during treatment ideally stick with you. So even after you’ve stopped going to treatment, you take those lessons with you and can use them to help prevent the return of symptoms.”

There are also several resources on campus that cater to different student’s needs, including University Health Services, Counseling and Mental Health Center and the Longhorn Wellness Center, all located in the Student Services Building.

Students can call or visit UHS in person to discuss any health related issue and receive treatment. UHS providers can prescribe medication when necessary, but encourage students to meet with a counselor first to determine the best approach for mental health treatment.

As for the CMHC, students can access their triage services by phone or in-person to speak with an intake counselor to discuss their unique situation and the best course of action.

“There’s individual counseling, support groups and specialized sessions,” Eshelman said. “If a student’s symptoms are severe—such as persistent depression, suicidal thoughts, or difficulty functioning—they may be referred for a psychiatric evaluation to discuss the possibility of medication.”