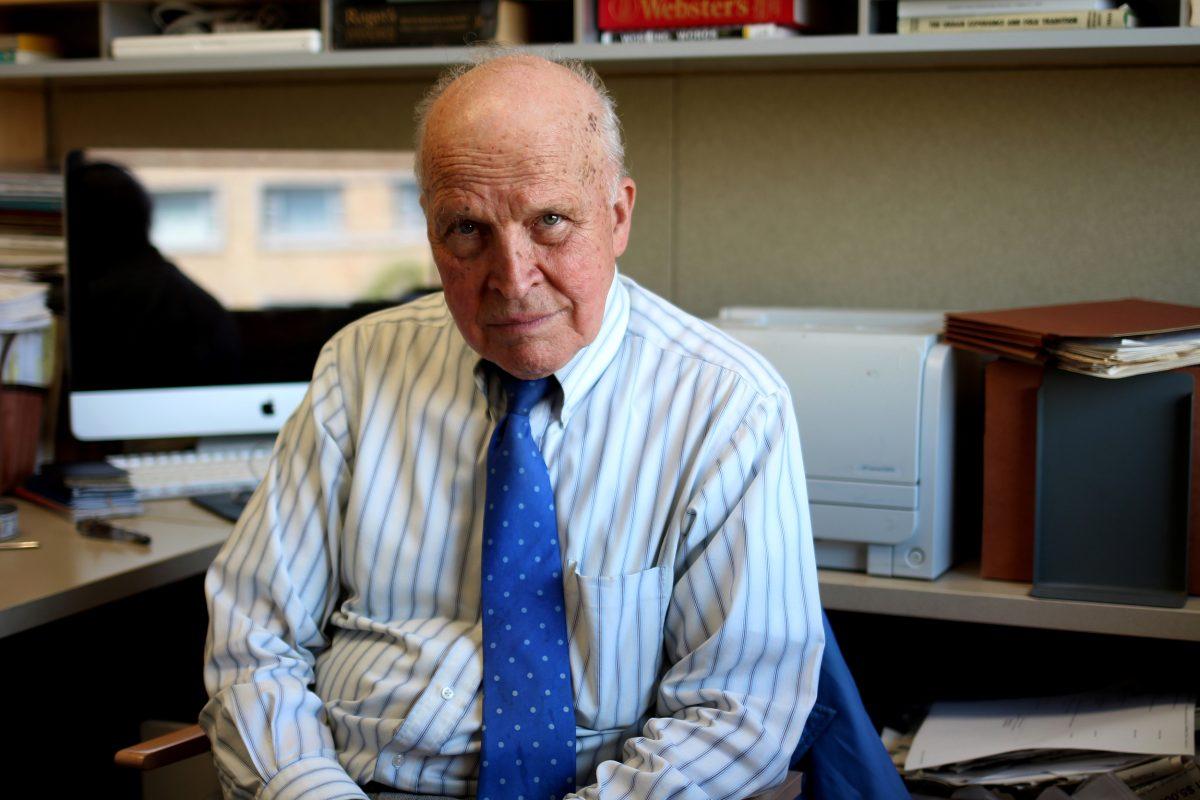

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in May 2014 for ORANGE Issue I. It has been republished online for the purposes of accessibility. Since its publication, Professor Gene Burd has retired from teaching at the University of Texas at Austin.

Story by Jane Claire Hervey

Photos by Hannah Vickers

In reports, the walk is usually described as a 2.5-mile trek.

However, UT journalism professor Gene Burd does not have a GPS, nor does he use an iPhone to calculate the shortest distance from his apartment on Barton Springs Road to the Belo Center for New Media. He knows the streets as avenues for communication, not transportation, and chooses to take the long way around — to look at the City, note its changes, check all of the parking meters for loose change and stop for a chat with a lot attendant by the Capitol.

In reality, the walk usually extends three to four miles, depending on whether Burd walks through campus or decides to make his way down the Drag to water a weed growing out of the concrete on the corner of 25th Street and Guadalupe Street.

He has made this walk almost every day for the last 42 years of his service at UT, with the exception of the few times fellow professor Dennis Darling convinced Burd to get in his car on a snowy day. Only when Burd feels dizzy or under the weather does he take the bus.

Almost 83 years old, Burd never learned to drive (he does not have a driver’s license), and bicycling is not his cup of tea. He says he fears he may be hit by a bicyclist one day, if he does not “fall to the wayside” and get hit by a car first. When the walk leaves him drenched in sweat or exhausted, he sometimes wishes he had taken a class behind the wheel.

But the walk is just part of Burd’s daily routine, as evidenced by the uneven rub of wear on the soles of his black loafers. Although the 21st Century may not understand, Burd finds his walk normal. When he retires in August of this year, his walk will not be his legacy. To that, Burd adds: “I don’t like the term ‘legacy.’ It sounds like you’re dead.”

Many who know Burd describe him as interesting. Once, a professor called him “quirky.” Following the incident, Burd lugged his thesaurus from his home to class to read out every definition of the word to his students. Although most of the meanings were negative, his class convinced him by the end of the hour that “quirky” can have positive connotations.

When asked to describe himself, Burd writes: 5’6” height, 145 lbs., single, Baptist, poet, writer-journalist, teacher (50 years).

Burd has never been married.

Some have made speculations about the silver band he wears on the ring finger of his right hand. He was in love once, but the ring is not for Dola Mae, the summer fling Burd let slip away in pursuit of his career when he was 19.

The ring was a gift. In 1964, the mentor who oversaw Burd’s dissertation at Northwestern University gave him the shiny piece of metal to congratulate him for the completion of his Ph.D. The ring has covered centimeters of his skin, whitening the flesh beneath it to conserve a memory, for the last 50 years. Burd still has his dissertation, too, in two thick, leather-bound binders on the top shelf of his office. His Ph.D. research on the demolition of the famed Hull House and Chicago’s urban renewal project in 1963 epitomizes the focus of his scholastic career. Once a resident of Hull House, Burd knew and respected the housemother, intellectual and activist Jane Addams. When Chicago gentrified that part of the city, only one of the Hull House’s 13 buildings, which had served as a hub for progressive thinking and higher education, were left standing. Although memorialized by a plaque and a museum now, this destruction led Burd to question communication in urban settings and the way humanity chooses to preserve the past.

After finishing his Ph.D. and leaving Northwestern, Burd taught for four years at Marquette University and then three years at Minnesota University. In 1972, a two-sentence acceptance letter to teach city and government reporting at the University of Texas brought him to Austin. Looking back at his four-decade career teaching UT journalism courses, Burd says, “I kept my promise.”

That career move did not mark Burd’s first visit to the “Live Music Capital of the World.” After graduating from UCLA, Burd was stationed in Germany as a member of the U.S. Army’s artillery. When he returned to the States, he spent much of his time before graduate school hitchhiking across the country. With a suitcase and little money, he hitched a ride to Austin and stayed at the Salvation Army, which was then located on 2nd Street and Congress Ave. downtown. His thumb got him to Kansas City another year, where he procured a job at Ernest Hemingway’s alma mater, the Kansas City Star.

At some point, he ended up working on a dude ranch in the northern reaches of the U.S. — a part of his life documented by a photo of Burd in a cowboy hat and a pearl-snap, black- and red-ribbed button-down. Professor Darling now owns the historic shirt. Burd raffled it off in an auction to raise money for students some years ago, and Darling bought it for $40.

Although Burd sticks to ties and slacks now, his expertise in rural life stems from his childhood.

He grew up in the mountains in the Ozarks. He had brothers and sisters, but the reality of rural poverty took its tool. His mother died in childbirth, and Burd was separated from his siblings at a young age. When Burd was 14, his father left to make money for the family as a migrant farm worker. Burd then moved to Los Angeles with his older brother to go to the Montezuma Mountain School in Los Gatos, California — from the land of buggies and outhouses to a city filled with cars and running water.

When he graduated, he did not have the money to go to college, so he pursued a reporting job at the Los Angeles Times. The paper, impressed by his work and dedication, awarded Burd a fellowship at UCLA. Burd credits this moment of generosity as the act of kindness that forever changed his academic career.

Perhaps it also speaks to the driving motivation behinds Burd’s monetary contributions to scholarship.

In 2002, Burd donated $28,300 toward an annual $1,000 award from the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AJEMC) for graduate students in Science Communication, Environmental Health and Risk studies. He helped to create the award in memory of Lori Eason, a graduate student who died in 2002 while trying to get her dissertation in media reporting on toxic waste disposal. Burd had helped Eason with her studies and considered her a kindred spirit in the journalism department. “I still miss her,” he says.

In 2004, Burd founded the Urban Communication Foundation, an organization that facilitates and rewards research in urban media studies, with Gary Gumpert and Susan Drucker. The three met at a communications convention one summer, both parties already familiar with the other’s work. Gumpert and Drucker shared their interest with Burd in urban communication, as well as their aspirations for the topic to develop as an area of study.

Throughout what Gumpert and Drucker call a “magical,” 6-hour conversation, which ended with a night out on the town and a round of drinks, the group made an undeniable connection. Burd told them to call him when they returned to New York City from the convention to continue their discussion and develop plans for further collaboration.

The following week, Drucker and Gumpert phoned Burd’s landline, and, in his signature quiet voice, Burd let them know he wanted to fund the beginnings of an organization for urban media studies — what is now the Urban Communication Foundation. Over the last ten years, Burd has donated $1,020,000 to endow the program and create grants for like-minded urban studies scholars. Two of the Urban Communication Foundation’s awards are in his name: the Gene Burd Outstanding Dissertation in Journalism Studies Award and the AJEMC Gene Burd Urban Journalism Award.

For Gumpert and Drucker, who head the foundation, Burd’s contributions have changed the face of their careers. “Never underestimate Burd,” Gumpert and Drucker say in unison.

Never underestimate is right.

In 2007, Burd donated $500,000 to the Junior Statesman of America Foundation for the annual Institute on Media and Politics for high school students in Los Angeles.

In 2009, he gave $30,000 to the Journalism Studies Division of the International Communication Association to award an annual prize for Ph.D. dissertations on urban communication.

In 2010, he pledged another $50,000 to the Urban Communication Foundation for administrative and conference costs and an annual, international “communicative cities” award.

Over the last ten years, Burd has donated $1,608,300 to higher education. When asked where the money comes from, Burd says, “I didn’t win the lottery. I didn’t inherit it. I saved it.”

One of the lowest-paid professors in UT’s journalism department, Burd’s frugality has made him a healthy sum of money throughout his career. A plastic jar filled with pennies, nickels, dimes and quarters sits on the dining table of his apartment, surrounded by papers and poems from his younger years. After every morning and evening walk, Burd dumps the loose change he finds — or maybe a $20 bill on a lucky day — into the container. At the end of every year, he cashes in about $300.

He did not purchase most of the items in his apartment, either. Burd saved the floral print, blue and purple couches from a neighbor who tried to throw away the furniture during a move. The rooster figurines on his coffee table are gifts from former students who discovered Burd’s love for poultry. As for his shoes, he bought them years ago. The two different hats he wears on his walks are so old he does not remember where they came from. His prized possession is a picture of the Earth from space, a sheet ripped out of an old magazine framed on the wall in his nook of a dining room. He holds on to that photo, because that was the first time he could verify that the Earth was round, although walking anywhere makes the planet feel flat — “amazing,” he says.

Aside from that photo and a couple of paintings, only neat stacks of manila folders and old cardboard boxes line the walls of his home. Filled with papers, from ones he has written to newspaper clippings, Burd has aggregated a tangible history. He sometimes takes these artifacts with him to his classes, showing students old reports from the 60s that correspond to current events and bringing photos from the time he worked on late President John F. Kennedy’s campaign.

Some of the stories do not have supplementary photos, like the time he caught “the pooper,” a graduate student who used to regularly relieve himself on the roof of the CMA building years ago. Although this story usually garners a laugh from his classroom, like most of Burd’s tales — Burd often says he “hits the nail with a sledgehammer” — he urges students to regard the anecdote with sympathy. The man, who was later found to have a mental health problem, was arrested that day.

This depth of understanding and compassion translates into his contributed work, as well. Burd helped to develop the first classes for minorities’ studies at UT. His research and book, “Jacob Fontaine (1801-1898): From Slavery to the Pulpit, Press and Public Service” on Jacob Fontaine — a Baptist preacher, newspaper publisher and community leader in the late 1800s, who was originally born into slavery — helped get the man’s name into the history books. He served as a liaison for the AEJMC’s Committee on the Status of Women in 1978. On top of that, his studies have been published more than 74 times in different newspapers, magazines and books (not including the contributions he made to the Encyclopedia Britannica). In his meticulously compiled resume, half of its 28 pages list bullet after bullet of the many presentations he has made at different colleges all over the country. The man’s biography can even be found in Marquis’ “Who’s Who in America.”

And if you ask him a question about anything, he usually has an answer.

For these reasons, former UT magazine professor Dave Garlock pushed to get the AJEMC award, the Gene Burd Urban Journalism Award, in Burd’s name.

For these reasons, Professor Dennis Darling, gives Burd, also known for his sweet tooth, a bag of candy every Christmas.

For these reasons, UT journalism student Dylan Baddour and his band surprised Burd and played his favorite hymn outside of the Belo Center for New Media one night.

For these reasons, Lydia Neuman, a grad student at UT, visits Burd in his office, bringing him a movie to watch or asking him for his thoughts on her dissertation.

For these reasons, former student Lou Rutigliano, now on staff at DePaul University, had the motivation to finish his Ph.D. under Burd’s guidance.

For these reasons, journalism senior Katie Paschall brought Burd his favorite dessert, a pecan pie, on his last day of class.

For these reasons, a group of six students and two professors, Kevin Robbins and Burd’s office neighbor, Bill Minutaglio, walked with Burd on the morning of May 1 from his home to the University for his last day teaching. Burd gave them a special tour of the City, waving notecards he had prepared at every stop. To make sure his makeshift “class” for that morning did not miss anything, Burd had made the walk the night before, ascertaining he included everything he knew.

Because it’s not the walk that makes the man.

It’s the man who makes the walk.